WID Biafran Airlift People

From Rpcvdraft

The World Is Deep - Continued

Biafran Airlift People David L. Koren, Nigeria 9 (1963-1966) March 2007

For R&R on Sao Tome the four of us UNICEF Volunteers - Larry, Barry, Leo, and I -explored the limited number of roads, and we cruised around the island on a fishing boat, with dolphins riding the bow wave. Some who went scuba diving said the sea was teaming with life. Local restaurants served a plentiful variety of seafood. Large crabs moving back and forth to the sea would cover the roads morning and evening. We went to a beach at the Bay of the Seven Waves (Baia de Sept Ono), a beautiful sandy bay with no one there but us. I saw mud skippers, fish that come out of the water and scoot purposefully across the sand for a time.

We ate and drank at places like the Hotel Salazar, high on a hill overlooking the bay, the town, and the Aerogare. Most of our daily meals were taken at Senor Costa’s, where we also rented our rooms. There were afternoon snacks at the Baia where they served Cuca a Copo, a Portuguese beer, and sausiga, which was something like a hot dog. From the Baia we could look across the bay and watch planes landing. Our old planes were all propeller driven, but about once a week a DC8 jet landed with some cargo or dignitaries. For more formal meals we dined at the Café Yong. [[ At these places we met the others who had gathered for this airlift. Missionaries. Mercenaries. Air crew and mechanics. Portuguese. Biafrans. Diplomats. Journalists. Africans of Sao Tome.

The mercenaries preferred the Hotel Salazar, the high ground. Most of them had little to say: they sat quietly and drank and watched. They were from South Africa, Rhodesia, Germany, Britain. Johnny Correa, a Puerto Rican American from New York City, breezed in once in a while, always ebullient. Taffy Williams, who looked something like Peter O’Toole from Lawrence of Arabia, gregarious for a clandestine fighter, boasted of their exploits. He told of Steiner leading a few Biafran fighters through enemy lines to blow up some planes in Enugu. He said that Biafrans were the best fighters in Africa. “With a company of men like that we could make it all the way to the Mediterranean, and no one could stop us.” I thought, why the Mediterranean? Why not Lagos?

Williams’ fingers were stained yellow and brown from heavy smoking. My wife had joined me by then. She told him that he should stop smoking because it was bad for his health. He nearly choked to death on a coughing fit provoked by laughing. He talked of a code of honor and behavior among mercenaries. They respected their fellow fighters, and they respected the women of their fellows. So he said. But I was surprised when the South Africans and Rhodesians treated my wife with great deference – she’s African American. I wonder, did they think I was a mercenary?

The four of us United Nations Volunteers would sit at Costa’s and talk about the motivation of those who came to the airlift. Some people were there to make money. Many were there because they were compelled by their religion to help the poor and suffering in the name of God. Yet many of these, missionaries included, openly distained or detested Biafrans. It was an abstract duty and the objects of their charity were irrelevant.

For some others who engage in charity I think that there is a set of expected behaviors between those who give help and those who receive it. The givers see themselves as somehow “above” those who receive, and they expect some acknowledgement of that status. Years later, when I worked in a deli on Second Avenue in New York, a man brought a bum in off the street and ordered a “hero” sandwich for him. I piled extra meat on it, knowing what was coming. As the bum ate he kept his head down and flicked his eyes up to his benefactor once in a while. The giver of the food then expected that he had the privilege, or the duty, to lecture the man on his life and how he should improve himself. More years later, when I worked in a mental hospital, a patient told me that he felt as if the staff did not want him to get better, because then they would not be “better” than he was. Their own needs required that distinction. The bum and the patient were victims of charity.

Biafrans did not behave in the expected ways. They were grateful without debasing themselves. They accepted aid and remained proud.

Another UN volunteer had been on Sao Tome before we arrived. He left in disgust, labeling the whole operation as “The White Man’s Burden’s Last Stand.”

It did not occur to the four of us, not then, to consider why we were there. Barry, Leo, and Larry had all been PCVs in Nigeria, although I didn’t know them then. Barry and Larry were about my age, 27, while Leo was about 50. He was a WW II veteran, who had been wounded by artillery fire.

One man I met, Johnny Moloco Dentista, belonged to no category. He was a small, poor, middle-aged, bald, Italian Jew with a little black bag full of dental instruments. He was an itinerant, meandering from place to place providing basic dental care to those who had none, strong enough within himself not to require payment or homage. He came out of Biafra, and I last saw him headed for Brazil to work with Indian people up the Amazon.

A lower level official from the U.S. State Department came through Sao Tome on a fact-finding mission to Biafra. Over a beer at the Baia he said, “What amazes me is how all of you relief people have swallowed the Biafran propaganda about starving children.”

As an aviation job, the Biafran Airlift attracted a fraternity of fliers from all over the world. They were British, American, Canadian, Scandinavian, and German crews and mechanics. ARCO hired a DC7 captain from Lapland who used to herd reindeer. Crews from Iceland were there flying off the equator. A few men had recently flown with the other big aviation job at the time, Air America in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. The CIA had conducted a food relief operation in Laos with Air America. But no one talked about that, much.

I liked the Icelandic guys. They taught me how to pronounce Reykjavik - it took a lot of practice. When they first arrived and learned that they were to fly over Biafra without navigation lights, they refused. It was too dangerous. No one had told them anything about flying without nav lights. Then someone told them that if they used lights, the Nigerians would shoot at them. “Oh. Okay.” And they flew.

I flew back from Uli with them one night. I was sleeping in the back of the empty plane when I woke up floating in air. Leo drifted a few feet away, suspended face down with his hands crossed in front of his face, elbows up, eyes wide. After several seconds we settled back down. I imagined that we were plunging into the sea. The flight engineer opened the cockpit door and peered back at Leo and me to see if we were all right. When he saw that we were not hurt, he smiled. “The pilot wanted to make joke on you.”

I said, “You mean, he did that on purpose?”

“Yes! Yes!” nodding with delight. The pilot had arced the plane up into a ballistic trajectory, and for a brief time we were in freefall, zero G. Thanks to them I got to experience weightlessness without ever becoming an astronaut.

Barry and Larry often worked as a team, and Leo and I as a team. On a night that Barry and Larry were flying, Leo and I were drinking with the ARCO mechanics. There was Arnie the Swede, Helmut the German, Smyth the Englishman, and three or four other Europeans. They complained about being overworked, that it was too much for the handful of them to keep those old planes flying. Leo and I said that we could turn a wrench, and we would be glad to help them if they showed us what to do. Chi nyere m aka. “God gave me hands.” And I can use them.

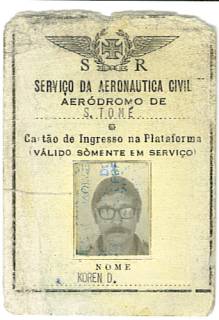

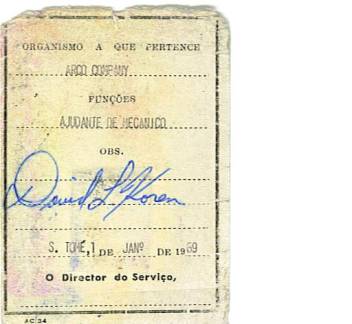

The next day ARCO hired us as help mechanics, and the Portuguese airport authorities issued us flight line IDs as Ajudante de Mecanico. And so we became more formally connected with the airlift, not just nebulous Field Service Officers.

ARCO paid us $25 a day, $50 if we flew into Biafra. Meanwhile, UNICEF started us off at $50 a week. They said they had no idea what we really needed, so if we wanted more, just ask. So we asked for $75 a week, and that became our volunteer allowance. By comparison pilots were paid $500 per flight. Copilots and engineers got $300. DC7s were fast enough to make three runs on a good night; $1500 a night was good pay in 1969. However, there was no insurance, and if you went down, the churches had never of you. At the end of each week I lined up at the pay table with the other ARCO employees. I have never seen so many $100 bills in my life. Dollars became common currency on the island, with the dollar bill used as a 7 Escudo note.

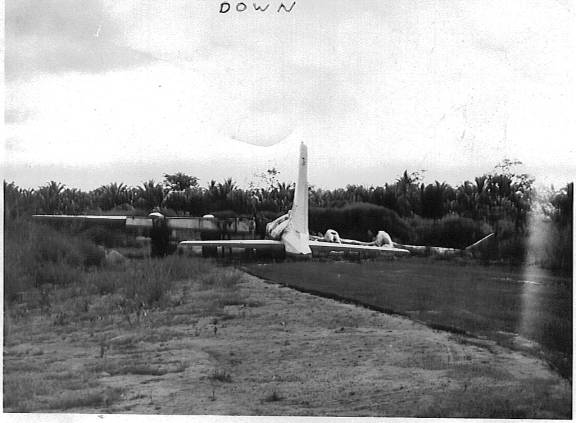

We began our career as mechanics by removing parts from the damaged DC7, noting carefully how we did it. Then we would ride into Biafra with the first flight, and work all night removing the same parts from another DC7, which was down at Uli, and then come out with the last flight. The downed plane had had mechanical trouble and couldn’t take off. The next day the Mig shot it up. The right wing and the fuselage burned; remarkably the left wing was still intact, with fuel still left in the wing tanks. Leo and I washed grease off of our hands by turning a petcock under the wing and letting the gasoline run over them. It was 140 octane aviation gasoline, very volatile, and it made your hands cold, even in the tropical heat.

Leo. When I look back on all this, I’m sure I do not know why Leo was with us. As a wounded WW II vet and a PCV he had already done service in this life. He didn’t seek adventure, nor fortune and glory. He didn’t brag. He never did say very much. Sometimes he would cock his head to one side, squint, and chuckle. On a hot, dry, still afternoon, as we worked quietly turning wrenches, he said, “In South Dakota it gets too windy to haul rocks.”

One other hot afternoon, while I was on top of a flimsy aluminum ladder with my hands stretched way back in the engine, up to my armpits, I looked to my right and saw Leo open the petcock and wash his hands – with a cigarette in his mouth.

“Leo!” I screamed. “Get away from there!”

“Huh? Oh.”

WID Reporting of the Biafran Airlift Next WID A Day in Biafra