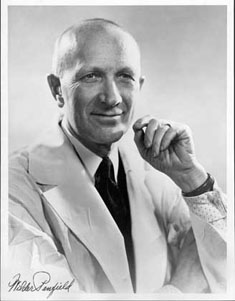

Wilder Penfield

From Psy3241

Wilder Penfield, the famous Canadian neurosurgeon, lived from 1891-1976. He wrote an autobiography titled No Man Alone: A Neurosurgeon’s Life published in 1977 in which he describes his life as a “great expedition of exploration”, one that would take him into the workings of the human mind, with emphasis on connections between science and the human soul (Penfield, 1977, p.329). Penfield, along with other famous surgeons such as Libet, Sperry and Gazaniga, laid the foundations for our understanding of the human cognitive unconscious (Restak, 2006). At the time, electrical stimulation of the brain established a new ways examining human cognition and behavior. He believed that access to the brain’s records was possible through electrical stimulation to the affected part during surgery (Sacks, 1995). He performed extensive brain surgeries on patients while they were on local anesthesia, which allowed them to remain awake and responsive to his questions. He discovered that all types of sensations, including images and memories, were elicited by stimulation of the brain and he was able to begin mapping the various parts of the cortex responsible for such elicitations (Ramachandran, 1998). He reported that patients experienced recollections of actual experience, which were evoked during seizures of the brain. This lead the patients to re-experience, in a way, very specific events, such as when they were looking at a door, or listening to a certain song (Sacks, 1995). Penfield termed these “experiential seizures”, what scientists now know are the repetitive elements of seizures that produce dreamlike states. Penfield and his colleagues, through electrical stimulation of the temporal lobe in patients with epileptic seizures, were able to discover connections between the amygdala and emotion (Damasio, 1994). One of his most notable contributions was his discovery of the “sensory homunculus,” the topographical representation of the human body that is mapped onto the surface of the brain lying in the sulcus between the somatosensory and motor cortices. The map is not entirely continuous and some body parts are over-represented. This reflects the fact that certain parts of our bodies, such as the lips, require finer discrimination and remain more sensitive to stimulation than other parts, such as the knee.