H.M. (patient)

From Psy3241

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

| + | == Outside Resources == | ||

| + | [http://www.psych.neu.edu/stellar/lab/people/MST/Hipp/HM.html H.M.] | ||

[[Category:Neuropsychological profiles]] | [[Category:Neuropsychological profiles]] | ||

Revision as of 20:56, 24 April 2008

H. M. is the single most famous case study in the history of neuropsychology. H. M. is an anonymous memory-impaired man, who is only referred to by his initials of H.M. (his real name was Henry). H. M. has one of the most severe cases of amnesia ever recorded, and has been observed by over 100 researchers for over 40 years.

Contents |

History

H.M was born in Hartford, Connecticut in 1926. He suffered from severe epilepsy, which has often been attributed to a bicycle accident at the age of 9, where he lost consciousness for 5 minutes. He began experiencing mild seizures, and had his first major seizure on his 16th birthday. He also had a family history of epilepsy stemming from his father's side. Into his late 20's, H.M. was experiencing up to 10 seizures and blackouts a week. His seizures were becoming incapacitating and he seemed to be unresponsive to anti-epileptic medications, even at maximum dosages.

Surgery

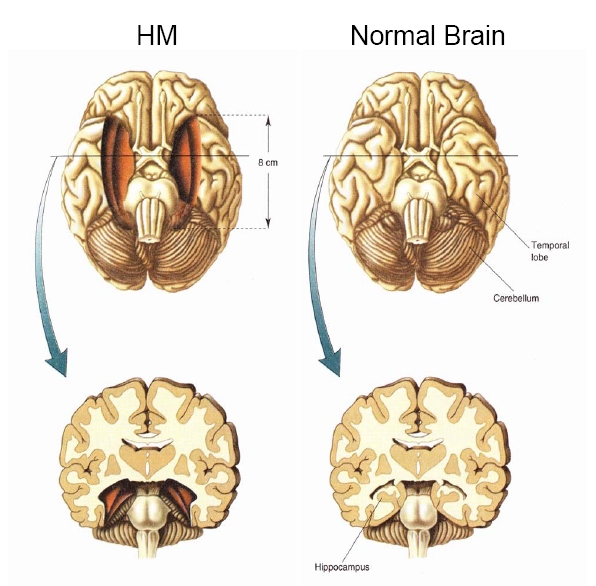

In 1953, at the age of 27, H.M. was referred to William Beecher Scoville, founder and director of the Department of Neurosurgery at Hartford Hospital. Dr. Scoville localized H.M.'s seizures to the temporal lobe, and on September 1st of that same year, he performed an experimental surgery on H.M. called a bilateral medial temporal lobe resection, removing parts of the temporal lobe from both hemispheres. The resection ultimately removed H.M.'s amygdala, entorhinal cortex, perirhinal cortex, and two-thirds of his hippocampus (see below).

Amnesia

H.M.'s surgery was successful in alleviating his symptoms, and he only had about 2 seizures per year after his surgery. H. M. was, however, left with profound memory difficulties. He has severe anterograde amnesia, and partial retrograde amnesia. He cannot form new long-term memories since his surgery, and cannot acquire new knowledge about anything going on around him or in the world. He does, however, know that he has some kind of illness, and that he is contributing something by allowing researchers to study him.

Despite H.M.'s amnesia, he remembers most all of his childhood memories, and can even correctly draw a foorplan of the house he grew up in. He also has an above average IQ of 118, and his capacity for language seems to be perfectly intact. H.M. has also proven to be able to learn simple sensorimotor skills: his performance improves with practice on a task involving him to trace a simple diagram by looking at its reflection in a mirror. H.M., of course, never remembers seeing or completing this task, though his performance is improving. H.M. also performs very well on cued-recall tasks. H.M. was even able to hold a simple job at the residential home where he lived, though he couldn't describe his job after working there for 6 months. H.M. is able to hold information in short-term memory for very short periods of time, showing that his working memory seems to be unaffected by the loss of his hippocampus. His main problem exists, however, in converting short-term memories into long-term memories, through a process called consolidation.

H.M.'s Contributions to Science

Studying H.M. has contributed a wealth of understanding of the organization of human memory systems. Most importantly it seems that the hippocampus is required for the formation of long-term memories but not for short-term recall. Also, once the long-term memory is permanently stored, the hippocampus is no longer required, for memory maintenance or retrieval. Furthermore, skill learning seems to be a special kind of long-term memory, not requiring the hippocampus.

H.M. Today

H.M. is currently living in a nursing home in Hartford, CT., and he occasionally travels to MIT for testing. He enjoys doing crossword puzzles and watching detective shows on television. Though he cannot really make any friends, since he can't remember them from ten minutes to the next, he does seem to have a sense of humor about his condition (taken from his autobiography):

When walking down the corridor at M.I.T. with Henry, Dr. Suzanne Corkin made the usual kind of small talk. "Do you know where you are, Henry?"

Henry grinned. "Why, of course. I'm at M.I.T.!"

Dr. Corkin was a bit surprised. "How do you know that?"

Henry laughed. He pointed to a student nearby with a large M.I.T. emblazoned on his sweatshirt. "Got ya that time!" Henry said.

H.M. leads a seemingly happy, yet confused life, and he never seems to know exactly how old he is (he guesses he is in his mid 30's, and is always surprised by his reflection in the mirror). He relives the grief of the death of his mother every time he hears about it, and though he doesn't remember his surgery, he knows there is something wrong with his memory. H.M. suffers from osteoporosis, a side effect of phenytoin, the anti-convulsive drug he has been taking. Otherwise, he is in very good health. Though death is of course inevitable, arrangements have already been made for post-mortem examination of his brain, which will undoubtedly reveal a great deal more about the anatomy of memory.