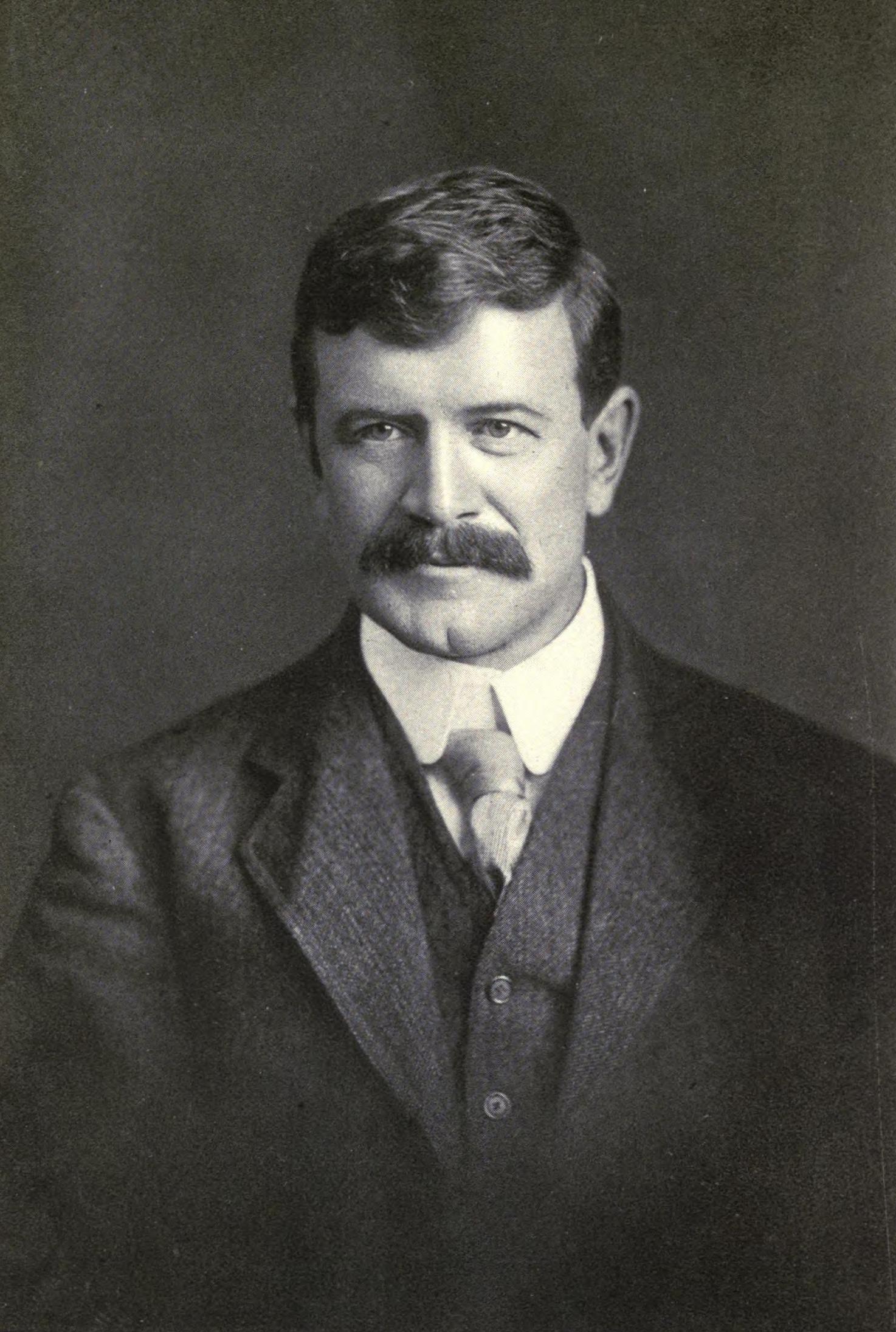

Stephen Leacock

From Kaiserreich

|

Sir Stephen Butler Leacock, (30 December 1869 – ) is an English-born Canadian economist, writer, politician and humorist.

Contents |

Early life

Leacock was born in Swanmore, near Bishop's Waltham, Hampshire, England, and at the age of six moved to Canada with his family, which settled on a farm in Egypt, Ontario, near the village of Sutton and the shores of Lake Simcoe. While the family had been well off in England (the Leacocks had made a fortune in Madeira and lived on an estate called Oak Hill on the Isle of Wight), Leacock's father, Peter, had been banished from the manor for marrying Agnes Butler without his parents' permission. The farm in the Georgina township of York County was not a success and the family (Leacock was the third of eleven children) was kept afloat by money sent by Leacock's grandfather. Peter Leacock became an alcoholic.

Stephen Leacock, always of obvious intelligence, was sent by his grandfather to the elite private school of Upper Canada College in Toronto, also attended by his older brothers, where he was top of the class and was chosen as head boy. In 1887, defending his mother and siblings against his father's alcoholic abuse, Leacock ordered him from the family home and he was never seen again. That same year, seventeen-year-old Leacock started at University College at the University of Toronto, where he was admitted to the Zeta Psi fraternity, but found he could not resume the following year because of financial difficulties.

He left university to go to work teaching — an occupation he disliked immensely — at Strathroy, Uxbridge and finally in Toronto. As a teacher at Upper Canada College, his alma mater, he was able simultaneously to attend classes at the University of Toronto and, in 1891, earn his degree through part-time studies. It was during this period that his first writing was published in The Varsity, a campus newspaper.

Academic and political life

Disillusioned with teaching, in 1899 he began graduate studies at the University of Chicago, where he received a doctorate in political science and political economy. He moved from Chicago, Illinois to Montreal, Quebec, where he became a lecturer and long-time acting head of the political economy department at McGill University.

He was closely associated with Sir Arthur Currie, former commander of the Canadian Corps in the Weltkreig and principal of McGill from 1922 until his death in 1933. In fact, Currie had been a student observing Leacock's practice teaching in Strathroy in 1888.

Leacock is both a social conservative and a partisan Conservative. He opposes granting women the right to vote, and dislikes non-Anglo-Saxon immigration and is a staunch champion of the British Empire and has gone on lecture tours to further the cause, he has long supported the notion of Imperial Federation saying "I am an Imperialist because I will not be a Colonial". He does however, support the introduction of social welfare legislation.

He was considered as a candidate for Dominion elections by his party, and in the 1935 election became a member of parliament, and is a tireless supporter of the Exiles and advocate for the liberation of England from the Union of Britain.

Literary life

Early in his career, Leacock turned to fiction, humour, and short reports to supplement (and ultimately exceed) his regular income. His stories, first published in magazines in Canada and the United States and later in novel form, became extremely popular around the world. It was said in 1911 that more people had heard of Stephen Leacock than had heard of Canada. Also, between the years 1915 and 1925, Leacock was the most popular humourist in the English-speaking world.

A humorist particularly admired by Leacock was Robert Benchley from New York. Leacock opened correspondence with Benchley, encouraging him in his work and importuning him to compile his work into a book. Benchley did so in 1922, and acknowledged the nagging from north of the border.

During the summer months, Leacock lives at Old Brewery Bay, his summer estate in Orillia, across Lake Simcoe from where he was raised and also bordering Lake Couchiching. Gossip provided by the local barber, Jefferson Short, provided Leacock with the material which would become Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town (1912), set in the thinly-disguised Mariposa.

Leacock was made a Knight Commander in the Order of the British Empire in 1930, he was awarded the Royal Society of Canada's Lorne Pierce Medal in 1934, nominally for his academic work (some critics have alleged that it should have gone to Frederick Grove citing anti-German sentiment as the reason).

Family Life

In 1900 Leacock married Beatrix ("Trix") Hamilton, niece of Sir Henry Pellatt (who had built Casa Loma, the largest castle in North America). In 1915 — after 15 years of marriage — the couple had their only child, Stephen Lushington Leacock. While Leacock doted on the boy, it became apparent early on that "Stevie" suffered from a lack of growth hormone. Growing to be only four feet tall, he has a love-hate relationship with Leacock, who tends to treat him like a child.

Trix died of breast cancer in 1925.

Bibliography

- Elements of Political Science (1906)

- Baldwin, Lafontaine, Hincks: Responsible Government (1907)

- Practical Political Economy (1910)

- Literary Lapses (1910)

- Nonsense Novels (1911)

- Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town (1912)

- Behind the Beyond (1913)

- Adventurers of the Far North (1914)

- The Dawn of Canadian History (1914)

- The Mariner of St. Malo (1914)

- Arcadian Adventures with the Idle Rich (1914)

- Moonbeams from the Larger Lunacy (1915)

- Essays and Literary Studies (1916)

- Further Foolishness (1916)

- Frenzied Fiction (1918)

- Keep Calm and Carry On (1919)

- Winsome Winnie (1920)

- The Unsolved Riddle of Social Justice (1920)

- My Discovery of England (1922)

- College Days (1923)

- Over the Footlights (1923)

- The Garden of Folly (1924)

- Mackenzie, Baldwin, Lafontaine, Hincks (1926)

- Winnowed Wisdom (1926)

- Short Circuits (1928)

- The Iron Man and the Tin Woman (1929)

- Imperial Economic Unity (1930)

- Marching to London: The Steps to Liberate the Motherland (1931)

- The Dry Pickwick (1932)

- Afternoons in Utopia (1932)

- Mark Twain (1932)

- Charles Dickens: His Life and Work (1933)

- Humour: Its Theory and Technique, with Examples and Samples (1935)