Ireland

From Kaiserreich

| ||||

| Motto Céad Míle Fáilte: A hundred thousand welcomes | ||||

| Anthem Amhrán na bhFiann ("The Soldiers' Song") | ||||

| ||||

|

| ||||

| Official Languages | Irish, English | |||

| Capital | Dublin | |||

| Head of State | Michael Collins | |||

| Head of Government | Eoin O'Duffy | |||

| Establishment - Indipendence from United Kingdom | ||||

| Declared | April 24 1916 | |||

| Ratified | January 1 1922 | |||

| - Republic of Ireland | October 24 1925 | |||

| Government | Semi-presidential republic | |||

| Currency | Irish pound | |||

| Area | 84 116 km² | |||

| Population | About 4 millions | |||

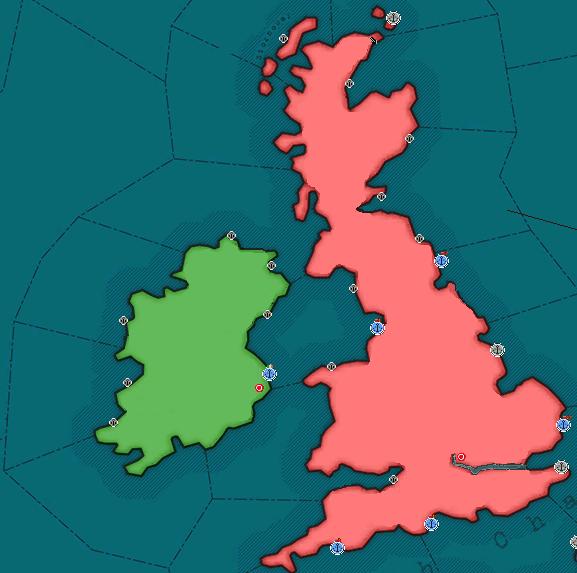

Ireland is a country in West Europe. It is located on the island of the same name, also known as Emerald Isle (the second largest island of the British Isles).

Contents |

History

Struggle for independence - 19th Century

Ever since coming under English (later British) rule, the Irish were rebellious and turbulent subjects, again and again rebelling in numerous ways and always being eventually put down and severely punished. The 19th Century saw the ancient Irish struggle take the form of a modern national movement - in which form it would at long last win the goal of Irish independence, though by a very tortuous and painful route.

In the early decades of the 19th Century Irish aspirations were expressed in the struggle for emancipation of Catholics, whose success enabled Irish politicians to be elected to the Parliament in London and play a significant role in British politics. Hailed at the time as a great achievement, it was nevertheless far from providing the Irish with a really satisfactory answer.

In mid-19th century the Emerald Isle was economically weak and easily troubled by crisis. Between 1845 and 1852 the potato harvest had been completely destroyed and a famine ravaged the land, leading to mass immigrations of Irish to the United States. The famine left a heritage of greater animosity towards Great Britain, seen as having mismanaged Ireland and not having taken proper care to offer relief in time and prevent the horendous death toll. Gradually, voices grew louder, demanding that Ireland have a government of its own - either as a sovereign state completely free of the British Crown, or at the least having a wide autonomy while still retaining Queen Victoria as their own monarch.

Some British politicians were ready to grant at least part of the Irish demands. The Liberal Prime Minister William E. Gladstone initiated the separation of the island from the Anglican Church in 1869 and a land reform in 1870. He failed in his attempts of pushing through a Home Rule for Ireland, however, and the political resistance in Ireland kept growing. The Home Rule League and the Irish Land League fought for autonomy as a first step towards independence. In the later part of the 19th Century, the Land League managed to considerably liberate Irish peasants from the yoke of absentee British landlords - a significant achievement which nevertheless failed to calm down the Irish.

1912 Crisis, Weltkrieg and the Easter Rising

In 1912 the British Parliament debated the long-delayed issue of Irish "Home Rule" - i.e., a considerable amount of self government while remaining under the British Crown. This move encountered tremendous opposition from the Protestant community concentrated in the historic Irish province of Ulster in the island's north-east corner - different from the Irish Catholics not only in religion but also in ethnic origin, being mainly descended from Scottish and English settlers implanted in Ireland since the 17th Century. These "Ulstermen" (and "Ulsterwomen") held mass rallies in stern opposition to Home Rule, organized a militia, openly subverted units of the regular British Army and explicitly threatend civil war.

As later events would prove, this stance would prove a massive miscalculation; within less than a decade the Ulster Protestants would face having exchanged a self-governing Ireland for a completely independent one. Moreover, having proclaimed themselves the most patriotic and loyal of all Britons, the Ulster Protestants' strong opposition to Home Rule in fact did a grave disservice to Britain, emboldening Germany to take a more aggressive stance in the following years, with the Irish unrest seen as a fissure in the edifice of the British Empire - which, indeed, would come crashing down within a decade.

These developments, however, were still hidden in the mists of the future at the time of the 1912 Crisis. Home Rule was formally adopted by the British Parliament, despite opposition in Ulster, with implementation set for 1914 - but it was suspended with the outbreak of the Weltkrieg, by whose end the situation in Ireland (as in the whole world) completely changed.

The Weltkrieg demanded the investment of most of Britain's military resources. Though the British still had enough soldiers in reserve to keep control of Ireland, this situation tempted radical Irish nationalists - disappointed and disillusioned by the suspension of Home Rule, and getting some direct backing from German intelligence – to embark on the Easter Rising of 1916, proclaiming a completely independent Irish Republic and holding out at the center of Dublin until overwhelmed by British forces. The rebels had no hope of a direct military victory, but did aim at lighting the spark of rebellion – in which they proved ultimately successful. The British indeed unwittingly helped this aim by insisting on execution of the uprising's leaders, thereby making them into popular martyrs and enhancing the appeal of Irish Republicanism among the masses.

It is noteworthy that James Connolly, a main leader of the Easter Rising, was a well-known Socialist theorist and agitator, or that many of his troops were in fact drawn from the militia of the Irish Trade Unions, who before tangling with British soldiers had the experience of fighting with Irish thugs and strike-breakers in the service of Irish employers. At the time, all this was obscured by their having been Irish nationalists fighting and dying for the liberation of Ireland. However, in later times – when the rise of Syndicalism would became a major world-wide issue, and in particular after the 1925 British Revolution convulsed Ireland's direct neighboring island – this would become a hotly contested political issue.

Later part of the Weltkrieg and General Uprising in Ireland

The British got only a brief respite by the crushing of the Easter Rising. It was the introduction of conscription (Ireland had been exempted from the introduction of conscription in 1916) to Ireland in March 1919 in reaction to Germany's Spring Offensive which set the spark - with Sinn Féin gathering in Dublin and proclaiming themselseves the Dáil and Ireland an independent nation. This declaration would be recognised by Germany and Bulgaria. (Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire refused, fearing that to recognise Ireland's independence would encourage nationalist rebellions at home)

Many of them were promptly arrested, the British furious at this act of outright rebellion in wartime - and the arrests set off the renewed armed uprising.

Michael Collins, the dynamic new political and military leader, rejected the strategy of 1916 - taking and holding a fixed position - as suicidal against the overwhelming British regular forces. Instead, he embarked on a highly effective campaign of urban guerrilla warfare, his "flying columns" hitting the British by stealth and ambush.

The dramatic collapse of France had numerous effects on the Irish struggle. The clear evidence of Britain in deep trouble and likely to lose the war greatly raised the morale of the Irish rebels and brought new recruits to their ranks. Moreover, the new situation in France enabled German Intelligence to send arms to the Irish rebels by fishing boats from the shores of France, far simpler and cheaper than by U-boat, resulting in a greater flow of arms.

On the other hand. the British Army sent many of the units evacuated from France to Ireland, hoping to drown the rebellion by sheer force of numbers. This, however, created unexpected complications. The soldiers arriving in Ireland were the veterans of long and harsh trench warfare - however, in trench warfare one nearly always knows where the enemy is, and the British troops found it difficult to adjust to guerrilla war where an attack could come at any time and place - even when soldiers on leave stroll down the street of an English-speaking town.

The troops, already bitter about the fiasco in France, reacted very furiously to the killing of comrades by "the treacherous Irish" and often resorting to indiscriminate retaliations, sometimes amounting to full-fledged massacres. These served to inflame the general Irish population and make also those who originally stood aside side with the rebels. Altogether, the war developed into a bloody stalemate - the Irish could not directly eject the far more heavily armed British troops from their soil, but the British could not break the rebellion.

A further complication arose with regard to the Irish soldiers evacuated from France, whose loyalty was suspect. Most of them were not taken back to their home island, but were kept cooped up at camps in England, frustrated, angry and often on very bad terms with surrounding English population. Some of them mutinied and were harshly punished. Others were disbanded, whereupon many of them joined the rebels in Ireland - some even managing to take guns with them.

Peace Treaty and the Irish Free State

The war in Ireland was not formally part of the Weltkrieg and in theory the Peace with Honour, respecting Britain's imperial possessions, left the British a free hand to continue their efforts to retain their power in Ireland. In fact, however, the Irish war was clearly a war by proxy with Germany, which provided full backing to the Irish rebels and seemed bent on continuing to do so.

By 1921, the Irish war was already considered futile and highly unpopular with the war-weary general British public, and continuing with it would have risked the position of the British government, already shaken and weakened by its responsibility for defeat in the war. Therefore, negotiations between the the British government and the Irish rebels started immediately upon signature of the treaty with Germany, and it was not long before a peace treaty was signed.

A major sticking point concerned the areas in north-eastern Ireland with a concentration of the Protestant Unionist population, which was staunchly opposed to the Irish rebellion and wished to remain part of the United Kingdom. British negotiators argued that their wishes should be respected and several counties with a Protestant Unionist majority should be given the right to "opt out" of being part of the independent Ireland.

In other circumstances the British might have strongly insisted on this point. However, in the circumstances of late 1921 their negotiating position was weak. Michael Collings, personally heading the Irish negotiating team, could credibly threaten to continue the war, backed by Gemrany, unless the British gave up their rule in "all of Ireland, all thirty-two counties without exception" and "let the Irish deal with each other as brothers".

The British finally gave in on this cardinal point, and under the peace treaty all of Ireland was ceded to the rebels. As could have been predicted, the Ulster Unionists reacted with outrage, accusing the British government of "gross betrayal" and vowing to continue the struggle by themselves - their position echoed by some British public figures such as the poet Rudyard Kipling. Thus, even with the British ceding power, asserting actual authority in Ulster would be far from easy for the new Irish government.

To mollify the British, Collins was ready to be flexible on a second major issue - the new country to be established and named the "Irish Free State" would remain formally part of the British Empire, and the British King would be its the Head of State. Neither Collins himself not his followers liked this provision. However, he pointed out that "for the first time in seven hundred years, there would remain not a single English soldier anywhere on the soil of Ireland" and that "ending that last immaterial vestige of their domination" could be left for later.

After the signing of the treaty in December by Collins, Griffith and the rest of the treaty delegation, the Free State was established on January 1 1922. Michael Collins became Taoiseach and leader of the Irish Free State.

While a civil war over the treaty was avoided, it would lead to the collapse of Sinn Féin as Ireland's main political party, with Collins' new government declaring their party name to be Fine Gael after Collins was expelled from Sinn Féin by party leader Éamon de Valera. A few months later, disagreements within the party over the Democratic Programme of the First Dáil would lead to another breakup, with many leaving Sinn Féin to form Fianna Fáil including Éamon de Valera, leaving Cathal Brugha as leader of Sinn Féin.

Sinn Féin looked to have totally collapsed, however their fortunes would turn around when in 1923 the prominent trade unionist James Larkin who had left Ireland after the failure of the 1913 Dublin Lockout returned from America and took control of the Labour Party, attempting to take advantage of Ireland's unstable state and foment a syndicalist uprising as in France. Fine Gael would ban Labour, leading to many joining the rump Sinn Féin, revitalising the party. Larkin himself would secretly form a new group with radical socialist Irish republicans and ex-ICA volunteers known as Saor Éire.

Republic of Ireland

Declaration of the Republic

On October 24 1925 when the British Revolution broke out, Collins' government drafted a new constitution and declared the end of the Irish Free State, and the birth of the Republic of Ireland. Collins, who soon became the new republic's First President - a position he would continue to hold up to the present - stated at the time that "We owe much to Germany, and are grateful - but we owe much more to the courage, dedication and sacrifice of Irish men and Irish women". He asserted that "Even had Britain won the war, Ireland would have still gained her freedom". The last was often disputed as a piece of Irish Nationalist bragging, though lately some historians formulated credible hypothetical scenarios of how the Irish might have indeed won a struggle against a UK victorious in the Weltkrieg (though clearly it have been far harder.)

The declaration of the Irish Republic was the occasion of week-long celebration and public jubilation at Dublin and most other Irish cities and towns. However, at Belfast and other Ulster cities with big Protestant Unionist populations the reaction was completely opposite. Some ministers in Fine Gael also disagreed with the declaration and left the party to form the National Centre Party.

James Craig, addressing a mass rally in central Belfast, stated: "Thirteen Years ago ([1]), Ulstermen and Ulsterwomen gathered on this very spot to say a resounding 'No!' to Home Rule which is Rome Rule. Now we say an even more resounding 'No!' to Home Rule's monstrous Republican daughter. We here in Free Ulster have no part in any Republic. We are, and will remain, loyal subjects of His Majesty George the Fifth, as we were of his ancestors for three hundred years and more".

The poet Kipling, who also spoke at the rally, read out his poem "Ulster 1912" ([2]) and told the crowd "I came here on behalf of Englishmen and Englishwomen - and Welsh and Scots too - who have kept faith, who have not forgotten nor forsaken our brave fellows here in Ulster".

He was strongly cheered - but his words underlined that the rebellious Ulster Protestants had been abandoned by all but a small minority of Britons in the midst of the British Revolution, and could not count on any British help. And the Ulster leaders were undecided on whether to proclaim "Free Ulster" an independent state or cling to their status as part of a United Kingdom which turned its back on them - falling back on the ambiguous definition of Ulster as "A Free Province" .

The Northern Campaign

The open defiance by the Ulster Protestants gave Collins an ample pretext to use the National Army which he had been arming and training in the past years. Immediately upon reports of the Belfast rally reaching Dublin, the Dáil was convened for an emergency meeting, and voted unanimously to proclaim martial law in the six counties of North-West Ireland where the rebellion against the Republic was concentrated, and to authorize the government and armed forces to "take all necessary steps to restore the Republic's full authority in all parts of Ireland".

As Commander in Chief of the armed forces, Collins took personal charge of the expeditionary force, which assembled on the outskirts of Dublin and moved swiftly northward by road and rail, and reaching Dundalk and Newry without incident, being welcomed by mostly friendly population. But a bit beyond Newry, at the village of Bessbrook ([3]), the rail was cut and the road barricaded by hastily-assembled units of the Ulster Volunteer Force, which had rushed from Belfast with the aim of denying Govenment forces access to County Down.

The UVF forces numbered between 5000 to 6000, but except for a few machine guns had only light arms, and most of them were poorly trained and had no combat experience apart from street fights with Catholic militias (and sometimes with rival Protestant ones). When subjected to an artillery barrage followed by a charge of "the lumbering metal monsters" (i.e. the obsolete German tanks supplied to Ireland), they soon broke and run, in a full rout back to Belfast. Ulster veterans of the Weltkrieg, who had taken the precaution of digging trenches, were not so easily fazed - having faced worse in France. But with the Unionist line punched through, they had to beat a more orderly retreat in order not to be cut off.

After several more encounters ending in a similar one-sided way, Craig came to the reluctant bur inevitable conclusion that the Ulster Unionist forces could not face the government's heavily-armed forces in the open, and ordered them withdrawn from most of Ulster. Only token units were left in the smaller towns, with most Unionist fighters concentrated in "The two great redoubts of Ulster freedom, Belfast and Londonderry". These, it was announced, would be "defended to the death", and in the two cities Protestant quarters there was an intensive fortification work with streets barricaded and mined, supplies and ammunition laid in for prolonged siege and house-to-house fighting.

Collins, however, did not hurry towards a head-on confrontation. Government forces moved methodically to take control of the main roads and strategic positions, establish themselves in barracks and military bases left behind by the British, and enter into the Catholic quarters of Belfast and Derry (as they insisted on calling Ulster's second-largest city) where they got a hero's welcome from a population greatly harassed in the past several years. The Protestant quarters of both cities were eventually placed under siege, but the only place where an assault and occupation were ordered was the Port of Belfast, considered essential to block the Unionists from getting supplies by sea.

Unlike in the Bessbrook fiasco and other earlier encounters, the Battle of the Port was bitterly fought, accounting for more than half the total casualties of both sides in the Northern Campaign. Defense of the Port of Belfast had been entrusted to Unionist veterans of the Weltkrieg, mainly former members of the British Army's 36 (Ulster) Division ([4]) under such commanders as Robert Quigg who won the Victoria Cross for outstanding bravery at the Battle of the Somme ([5]).

Government forces were debarred from using their heavy weapons, which would have thoroughly wreaked the port. Their infantry had the unenviable task of chasing Unionist fighters across docks made into obstacle courses and winkling them out of warehouses and the holds of moored boats, which gave the defenders countless chances for ambushes and booby-traps, while derricks were made into deadly Unionist snipers' positions. The bloody fighting at the port gave a grim foretaste of what could be expected in the overall conquest of the fortified Protestant quarters, and seasoned war correspondents converging upon the scene from all over the world predicted that Belfast might rival Ypres as a city totally destroyed by war. Unionist militiamen who hated Collins' guts gleefully vowed to make the Republican leader "eat his own medicine" and subject him to the same kind of urban guerrilla campaign he had waged against the British.

Ulster Ceasefire and Political Compromise

With the whole world poised for news of bloody fighting in Belfast, Collins made a startling offer of an immediate ceasefire, inviting Craig to discuss terms - which the Unionist leader, after some hesitation, accepted. Negotiations were held at an abandoned house in no man's land, a large part of it in a personal discussion between Collins and Craig with no aides present and no minutes taken.

The ceasefire terms, published on the next morning, were considered quite generous to the embattled Unionists: Both sides to retain their positions until further notice; siege of Protestant quarters removed and free traffic of unarmed persons assured; Unionist militias not required to disband or disarm, nor to formally abjure their rebellion against the Irish republic, but only "hold themselves in readiness for regularization of their status".

Unionists and their supporters mostly celebrated the agreement as a victory of their "steadfast defense" and as "the vindication of the heroes and martyrs of the Port of Belfast". For his part, Collins was content to let them present it this way. On his return to Dublin, he faced the attack of a vocal minority in the Dáil accusing him of "a sell-out", making an impassioned speech to defend his policy:

"It was totally unacceptable that Ulster, one of the great historic provinces where so many momentous events of ancient and modern Irish history took place, be torn off the body of Ireland. This will not happen - Ulster is, and will always remain, part of the Republic of Ireland! (Applause). It was totally unacceptable that our Irish brothers and sisters in Belfast and Derry be subjected to harassment and persecution and mob rule, for the sole crime of being of the Catholic faith and of being strong supporters of our Republic. This will never, never happen again - the strong arm of the Republic is there to defend them, and will always be there to defend them! (Applause). These two major objectives having been achieved - achieved through the determination, courage and sacrifice of our soldiers - it would have been the height of madness, the worst of crimes, to burst into the Protestant quarters as bloody conquerors, angels of destruction. It would have been the worst of crimes against Ireland! (Applause). The Protestants of Ulster are not our enemies, however estranged we have become from them due to centuries of foreign rule and its nefarious schemes of setting Irish against Irish. The Protestants, too, are our fellow Irishmen and Irishwomen. Some of greatest and most glorious heroes of Ireland's history had been Protestants, such as Wolfe Tone, Robert Emmet and many others. It was for the sake of Irish Protestants that an Orange band was inscribed in the National Flag of Ireland, co-equal with the Green one. It is not by bloody conquest that we would win them to our Republic, but by patience and patience again!"

Collins won the subsequent vote of confidence by a very great majority. The Ulster Ceasefire also marked Collins' decisive victory over his opposition in Fianna Fáil, Sinn Féin, and the breakaway National Centre Party.

Situation as of 1936

After more than ten years of rule, in 1936 Collins leads the nation, riding on a wave of unbeatable public support, with only a minor coalition calling themselves the 'Democratic Opposition' opposing him. Officially its President, unofficially Michael Collins has become dictator of the Second Republic.

Politics

President: Michael Collins

Taoiseach: Eoin O'Duffy

Minister for Foreign Affairs: Kevin O'Higgins

Chancellor of the Exchequer of Ireland: Oliver J. Flanagan

Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform: Gearóid Ó Cuinneagáin

Director of the Directorate of Intelligence: Sean MacEoin

Director of Military Operations: Richard Mulcahy

Commander-in-Chief of the Irish Republican Army: Eoin O'Duffy

Commander-in-Chief of the Irish Republican Navy: Eamon Broy

Commander-in-Chief of the Irish Republican Air Force: Piaras Béaslaí

Military

Army

The Irish Republican Army was gradually reduced in the last years, as Canada and Union of Britain seemed less threatening as before. As of now it consists of three division, guarding Dublin and Belfast. However, many call for an expansion of the army, as lately both the British Syndicalist and the British Exiles appeared inclined to choose a more militaristic approach towards each other. If war will be declared, Ireland might be caught in the middle and might even be forced to choose a side.

Navy and Air Force

A serious naval or air program has never been attempted. The Republican Navy consists of only two destroyers while the Republican Air Force is basically non-existent.

Foreign Relations

Good relations with Italian Federation, United States and Germany.

Unfriendly relations with Union of Britain and Canada.

Culture

After the declaration of independence from the United Kingdom, Irish culture was finally free to express itself, with its mix of Celtic and Catholic traditions. Much of the Irish calendar still today reflects the old pagan customs, with later Christian traditions also having significant influence.