Prosopagnosia

From Psy3242

| (9 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

| - | '''Prosapagnosia''' is defined as the inability to perceive faces, or ''face blindness''. This rare disorder varies in intensity. One person with the disorder may not be able to recognize whether two pictures are of the same face or not, while another patient may affect recognition of one's own family members. In a most severe example, a person may no longer be able to recognize himself in a photograph or the mirror. | + | '''Prosapagnosia''' is defined as the inability to perceive faces, or ''face blindness''. It is a type of ''agnosia'', a term used in neuropsychology to mean ''lack of knowledge'' about a particular subject. The disorder has nothing to do with actual visual blindness, as the person is usually able to view everything else normally. It is a perceptual problem that prohibits people from being able to put the image of the face together as a whole. This rare disorder varies in intensity. One person with the disorder may not be able to recognize whether two pictures are of the same face or not, while another patient may affect recognition of one's own family members. In a most severe example, a person may no longer be able to recognize himself in a photograph or the mirror. These skills do not improve with practice or familiarity. Usually it is not limited to the recognition of individuals, but also of more basic facts such as gender and facial expression. The picture below gives the impression of what a person with prosopagnosia might see when looking at another person's face. |

| + | [[Image:prosopagnosia_03.jpg]] | ||

== '''Prosopagnosia and the Brain''' == | == '''Prosopagnosia and the Brain''' == | ||

| Line 15: | Line 16: | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| + | Through the use of many studies on the brain, including PET scans, it seems that prosopagnosia relates to damage to a particular part of the brain. There is an area on the right side of the brain that specializes in perception of people. These area, the ventral regions of the occipital and temporal lobes, have been found to be involved in perception of faces. It is suggested that posterior regions help to put together the individual characteristics of the faces, while the area in front of it aids in identification and memory of bibliographic information of the person to whom the face belongs. | ||

| + | In some cases, however, it is associated with bilateral damage, or damage on both sides of the brain. If the visual cortex is damaged on both side, prosopagnosia is not likely to be the only disorder. More generalized agnosias may occur, including the inability to recognize objects. This inclusion of the right brain extends from a lack of knowledge about faces, to a generalized lack of knowledge about objects in general. | ||

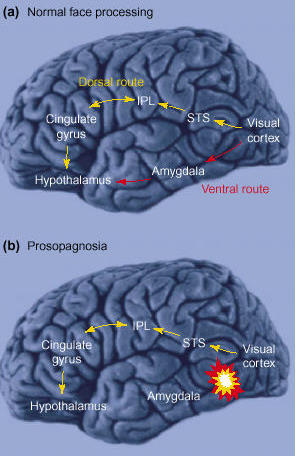

| + | Below the route of facial perception is described through the path of various parts of the brain. The dorsal route is intact, but in people with prosopagnosia, the ventral route is disturbed. | ||

| + | [[Image:Ellis-fig3.jpg]] | ||

| - | == '''Case | + | |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == '''Case Study''' == | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| + | |||

| + | At age 24, Michael was involved in a motorcycle accident where he hit a tree and was immediately hospitalized. Initially becoming "cortically blind," or blind because of damage to his occipital lobes and not to his eyes themselves, he slowly began to retrieve his vision after 17 months, beginning with the ability to see lights and finally recognizing letters and objects. His ability to recognize faces, however, remained lost. Along with a great deal of other symptoms and problems, prosopagnosia is something that Michael deals with every day. This is mainly due to the amount of dead tissue in his occipital lobes, most of which is concentrated in the right side of the brain. On top of inability to recognize faces, he had no ability to recognize visual patterns and certain objects. For example, he could copy a drawer of, say a turtle, if he did it area by area, but could not recognize what he had drawn. He could, however, recognize objects through tactile methods, or touch only. Michael became color impaired after the accident as well. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Michael suffered some severe social consequences from his prosopagnosia. As one could imagine, he was very frustrated with his syndrome, a lot of which was due to his memory deficiency after the accident. Obviously Michael's brain damage had an unfortunate impact on his daily life, and this provides a bit of perspective on a person suffering from prosopagnosia. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

== '''Further Information''' == | == '''Further Information''' == | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| + | |||

| + | The following link is to a site built by a woman with prosopagnosia. She describes in basic terms what she deals with on a daily basis, and some of the social consequences of the disorder. | ||

| + | |||

| + | http://www.prosopagnosia.com/ | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | This link brings you to the site for the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, which provides some explanations about dealing with the disorder. | ||

| + | |||

| + | http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/prosopagnosia/Prosopagnosia.htm | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The following link is to a YouTube video providing a summary of the disorder. | ||

| + | |||

| + | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZogbIvdgfzQ | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == '''References''' == | ||

| + | |||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The "further information" as well as the following resources were used for generating the information on this page. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Ogden, Jenni A. (1996). Fractured Minds. Oxford: New York. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Stirling, John. (2002). Introducing Neuropsychology. Psychology Press: New York. | ||

Current revision as of 04:27, 28 April 2008

Prosopagnosia

Contents |

Definition

Prosapagnosia is defined as the inability to perceive faces, or face blindness. It is a type of agnosia, a term used in neuropsychology to mean lack of knowledge about a particular subject. The disorder has nothing to do with actual visual blindness, as the person is usually able to view everything else normally. It is a perceptual problem that prohibits people from being able to put the image of the face together as a whole. This rare disorder varies in intensity. One person with the disorder may not be able to recognize whether two pictures are of the same face or not, while another patient may affect recognition of one's own family members. In a most severe example, a person may no longer be able to recognize himself in a photograph or the mirror. These skills do not improve with practice or familiarity. Usually it is not limited to the recognition of individuals, but also of more basic facts such as gender and facial expression. The picture below gives the impression of what a person with prosopagnosia might see when looking at another person's face.

Prosopagnosia and the Brain

Through the use of many studies on the brain, including PET scans, it seems that prosopagnosia relates to damage to a particular part of the brain. There is an area on the right side of the brain that specializes in perception of people. These area, the ventral regions of the occipital and temporal lobes, have been found to be involved in perception of faces. It is suggested that posterior regions help to put together the individual characteristics of the faces, while the area in front of it aids in identification and memory of bibliographic information of the person to whom the face belongs.

In some cases, however, it is associated with bilateral damage, or damage on both sides of the brain. If the visual cortex is damaged on both side, prosopagnosia is not likely to be the only disorder. More generalized agnosias may occur, including the inability to recognize objects. This inclusion of the right brain extends from a lack of knowledge about faces, to a generalized lack of knowledge about objects in general.

Below the route of facial perception is described through the path of various parts of the brain. The dorsal route is intact, but in people with prosopagnosia, the ventral route is disturbed.

Case Study

At age 24, Michael was involved in a motorcycle accident where he hit a tree and was immediately hospitalized. Initially becoming "cortically blind," or blind because of damage to his occipital lobes and not to his eyes themselves, he slowly began to retrieve his vision after 17 months, beginning with the ability to see lights and finally recognizing letters and objects. His ability to recognize faces, however, remained lost. Along with a great deal of other symptoms and problems, prosopagnosia is something that Michael deals with every day. This is mainly due to the amount of dead tissue in his occipital lobes, most of which is concentrated in the right side of the brain. On top of inability to recognize faces, he had no ability to recognize visual patterns and certain objects. For example, he could copy a drawer of, say a turtle, if he did it area by area, but could not recognize what he had drawn. He could, however, recognize objects through tactile methods, or touch only. Michael became color impaired after the accident as well.

Michael suffered some severe social consequences from his prosopagnosia. As one could imagine, he was very frustrated with his syndrome, a lot of which was due to his memory deficiency after the accident. Obviously Michael's brain damage had an unfortunate impact on his daily life, and this provides a bit of perspective on a person suffering from prosopagnosia.

Further Information

The following link is to a site built by a woman with prosopagnosia. She describes in basic terms what she deals with on a daily basis, and some of the social consequences of the disorder.

This link brings you to the site for the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, which provides some explanations about dealing with the disorder.

http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/prosopagnosia/Prosopagnosia.htm

The following link is to a YouTube video providing a summary of the disorder.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZogbIvdgfzQ

References

The "further information" as well as the following resources were used for generating the information on this page.

Ogden, Jenni A. (1996). Fractured Minds. Oxford: New York.

Stirling, John. (2002). Introducing Neuropsychology. Psychology Press: New York.