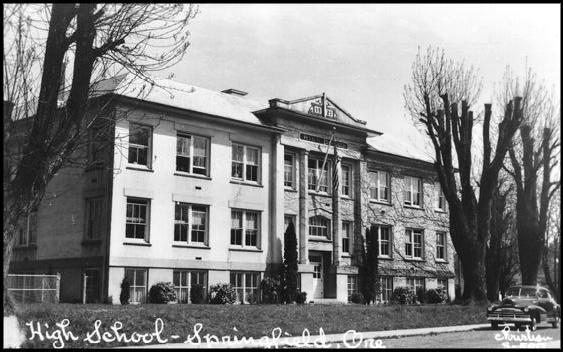

Springfield High School

From Lane Co Oregon

(→1910s) |

(→1910s) |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

==1910s== | ==1910s== | ||

| - | By [[1912]], 70 students had enrolled in the school. Early in the [[1913]]-[[1914]] school year, the students initiated a campaign to | + | By '''[[1912]]''', 70 students had enrolled in the school. Early in the '''[[1913]]'''-'''[[1914]]''' school year, the students initiated a campaign to |

encourage prospective pupils to enroll at SHS. They strung a large canvas downtown to advertise the school and even made | encourage prospective pupils to enroll at SHS. They strung a large canvas downtown to advertise the school and even made | ||

| - | personal visits to enlist more youths. By February, the student population nearly reached the 100 mark. According to the SHS Annual, "when on [[February 27]], it was discovered that the one-hundredth student was actually in attendance, the enthusiasm of the school knew no bounds and a holiday, to celebrate the occasion, was voted by the students and approved by the Board of Directors." The students then proceeded to parade the main streets of Springfield in the drizzling rain, led by a bugler and an array of banners and placards announcing the holiday.[2] | + | personal visits to enlist more youths. By February, the student population nearly reached the 100 mark. According to the SHS Annual, "when on '''[[February 27]]''', it was discovered that the one-hundredth student was actually in attendance, the enthusiasm of the school knew no bounds and a holiday, to celebrate the occasion, was voted by the students and approved by the Board of Directors." The students then proceeded to parade the main streets of Springfield in the drizzling rain, led by a bugler and an array of banners and placards announcing the holiday.[2] |

By all accounts, the student body of that year was a tightly knit group of friends who showed great enthusiasm for their school. | By all accounts, the student body of that year was a tightly knit group of friends who showed great enthusiasm for their school. | ||

| - | Junior [[Bailey, Walter|Walter Bailey]], the President of the Student Body, wrote an essay in the | + | Junior '''[[Bailey, Walter|Walter Bailey]]''', the President of the Student Body, wrote an essay in the 1914 Annual titled "Why |

| - | Springfield High Is the School for Me." Bailey, who attended [[Eugene High School]] as a freshman, wrote, "I have nothing to say against the Purple and the White, but I have a great deal to say for the Blue and the White. I can say without exaggeration that I never met a more congenial and cordial group of students than I found in Springfield." Bailey notes the lack of cliques at his school and the general spirit of unity among the student body. "We are many in number but one in strength and purpose."[2] | + | Springfield High Is the School for Me." Bailey, who attended '''[[Eugene High School]]''' as a freshman, wrote, "I have nothing to say against the Purple and the White, but I have a great deal to say for the Blue and the White. I can say without exaggeration that I never met a more congenial and cordial group of students than I found in Springfield." Bailey notes the lack of cliques at his school and the general spirit of unity among the student body. "We are many in number but one in strength and purpose."[2] |

| - | The student body of that era was an industrious group whose activities included the first Annual (1914) and the first student periodical, ''The Headlight'' (November 14). Deterred by the lack of athletic facilities, students resorted to the Literary Society; with 60 members, it was by far the most popular club in the school. The literary Society initiated a debating team, which won "victory after victory..." although it did not win the regional championship at Villard Hall in [[Eugene]]. A typical Literary Society meeting would include roll call answered by famous quotations, a musical performance on the piano or violin, and a debate that dealt with a current school issue. | + | The student body of that era was an industrious group whose activities included the first Annual (1914) and the first student periodical, ''The Headlight'' (November 14). Deterred by the lack of athletic facilities, students resorted to the Literary Society; with 60 members, it was by far the most popular club in the school. The literary Society initiated a debating team, which won "victory after victory..." although it did not win the regional championship at Villard Hall in '''[[Eugene]]'''. A typical Literary Society meeting would include roll call answered by famous quotations, a musical performance on the piano or violin, and a debate that dealt with a current school issue. |

The students and the small faculty (six teachers in 1914) often indulged in parties and receptions, which were frequently sponsored in the home of a teacher. Individual classes usually threw their own receptions (the Freshmen party or the Senior party, for example), and could expect a friendly amount of rivalry from the other classes, whose members were fond of crashing parties and creating mischief. | The students and the small faculty (six teachers in 1914) often indulged in parties and receptions, which were frequently sponsored in the home of a teacher. Individual classes usually threw their own receptions (the Freshmen party or the Senior party, for example), and could expect a friendly amount of rivalry from the other classes, whose members were fond of crashing parties and creating mischief. | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

The games were often disrupted when the freshmen were discovered lurking about the house. The upperclassmen would pause to chase them off then resume their activities. Later in the evening, however, someone sneaked up to the house, opened the kitchen window, and stole a "sack of sugar, a pail of syrup and a bottle of vinegar" that had been reserved for making taffy. The upperclassmen promptly accused the freshmen of the crime, and a great mock trial took place in the assembly hall of the school. In the end, the freshmen were found not guilty.[4] | The games were often disrupted when the freshmen were discovered lurking about the house. The upperclassmen would pause to chase them off then resume their activities. Later in the evening, however, someone sneaked up to the house, opened the kitchen window, and stole a "sack of sugar, a pail of syrup and a bottle of vinegar" that had been reserved for making taffy. The upperclassmen promptly accused the freshmen of the crime, and a great mock trial took place in the assembly hall of the school. In the end, the freshmen were found not guilty.[4] | ||

| - | At the head of all this activity were the charismatic figures of Walter Bailey, the popular leader with the polite smile, and Herbert Hansen, who must have received a great amount of mockery for his conspicuous ears. The two probably shared the sort of rivalry found between the classes: friendly but energetic. Both served as President of the Student Body (Baily in 1914 and Hansen in 1915) and both held the position of Editor-in-Chief of the new Annual (Hansen in 1914 and Bailey in 1915). On several occasions, both Bailey and Hansen filled the position of Literary Society President.[4] | + | At the head of all this activity were the charismatic figures of Walter Bailey, the popular leader with the polite smile, and '''[[Hansen, Herbert|Herbert Hansen]]''', who must have received a great amount of mockery for his conspicuous ears. The two probably shared the sort of rivalry found between the classes: friendly but energetic. Both served as President of the Student Body (Baily in 1914 and Hansen in '''[[1915]]''') and both held the position of Editor-in-Chief of the new Annual (Hansen in 1914 and Bailey in 1915). On several occasions, both Bailey and Hansen filled the position of Literary Society President.[4] |

The two would often find each other in disagreement over current issues. Bailey would generally support conservative notions while Hansen favored the more radical. In a Literary Society debate recorded in ''The Headlight'', Bailey held that "the school board of District No. 19 are vested with power and are justified in... regulation the social life of the High School students." Hansen argued against him and lost the debate. (In the mock trial mentioned earlier, Bailey acted as prosecuting attorney while Hansen bravely agreed to defend the low-life freshmen; in that instance, Hansen emerged the victor.) | The two would often find each other in disagreement over current issues. Bailey would generally support conservative notions while Hansen favored the more radical. In a Literary Society debate recorded in ''The Headlight'', Bailey held that "the school board of District No. 19 are vested with power and are justified in... regulation the social life of the High School students." Hansen argued against him and lost the debate. (In the mock trial mentioned earlier, Bailey acted as prosecuting attorney while Hansen bravely agreed to defend the low-life freshmen; in that instance, Hansen emerged the victor.) | ||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

Some of the class of 1915's activities reflect the blatant prejudices of the day. For instance, in an evening of dramatics sponsored by teachers, the students performed a 90 minute Minstrel Show wherein they blackened their faces with burnt cork and played such characters as Sambo. In it, Dinah, called "the Modern Joan of Arc," performed her famous speech "When Dey Enlisted Cull'ed Soldiers." The show concluded with "the roaring farce entitled ''Mr. Jackson's Servants,'' featuring Sambo, Dinah, Lizzy, Josey, and Lizah" as the servants. It is difficult to discover what became of those 100 students; more than likely, some died in the trenches of World War I. Others may be alive to this day.[4] | Some of the class of 1915's activities reflect the blatant prejudices of the day. For instance, in an evening of dramatics sponsored by teachers, the students performed a 90 minute Minstrel Show wherein they blackened their faces with burnt cork and played such characters as Sambo. In it, Dinah, called "the Modern Joan of Arc," performed her famous speech "When Dey Enlisted Cull'ed Soldiers." The show concluded with "the roaring farce entitled ''Mr. Jackson's Servants,'' featuring Sambo, Dinah, Lizzy, Josey, and Lizah" as the servants. It is difficult to discover what became of those 100 students; more than likely, some died in the trenches of World War I. Others may be alive to this day.[4] | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

[1] The Millers: History of Springfield High School, editor Pat Albright, 8-9. | [1] The Millers: History of Springfield High School, editor Pat Albright, 8-9. | ||

Revision as of 19:04, 17 October 2008

Contents |

History

Foundation

By 1854 Springfield had its first school, probably near 7th Street and B Street, and a teacher, Agnes Stewart. By 1870, the population of Springfield had grown to nearly 650 before the Oregon and California Railroad was persuaded to cross the Willamette near Harrisburg and go through Eugene. River navigators also could not get beyond the Eugene area to Springfield except during floods. The developments were a severe blow to Springfield to the extent that the population dwindled less than 400 by 1890.[1]

Although progress was slowed, Springfield continued to refine its town. In 1885 the two-room school house at Mill Street and D Streets had over 60 students. Eugene with the railroad and a university, was developing much faster as a service and trade center.[1]

For Springfield, change came in 1891 with a rail line and a new steel bridge. By then, Springfield had two schools in addition to three hotels, three churches, two groceries, a meat market, a shoe store, a drug store, two blacksmiths and a couple of general merchandise stores.[1]

Education was limited to the eighth grade, which was a concern for those who sought higher education at the university. It was also a concern for those who taught at the university. Incoming students were rarely prepared for the requirements of a university education and needed extra preparatory help. By the mid 1890s the University of Oregon president was encouraging the establishment of high schools to help serve this need. Eugene was already graduating more than 100 students from its eighth grade. Springfield had barely 10 percent of that number. Springfield High School began in 1898.[5] By 1900, the population of Springfield still languished around 350. However, the milling boom was beginning, and in 1902, a large modern and economical mill was built in Springfield by the Booth-Kelly Company. In less than 10 years the population of Springfield grew to about 2,500.[1]

It was not until 1905 that Springfield High was able to graduate its first senior - Merit Tuel. In 1907 no one graduated. By graduation time in 1908, the classes were again reestablished. According to the February 1909 edition of the student publication Nonpareil, it was apparently during this school year that the classes finally became organized into a student body.

"The students of the S.H.S. have organized a student body," the publication reported. "From now, remember that 'United we stand, divided we fall'," it concluded.

On January 26 of 1909 the student body elected Senior Lacy Copenhaver as their president, apparently the first student to lead Springfield High School.

The earliest records of SHS activities include reports or student performances. In an April 1909 edition of the student publication Nonpariel, Lloyd Emery, an SHS junior at the time, reports that the traditional senior play was expanded to include the entire school population to perform "The Devil in Society." Apparently late rehearsals were as common then as now. The writer went on to say, "it does not seem to agree with the High School pupils to stay up late for a few nights in succession, for the day after the play it kept the teachers busy keeping the pupils awake." He added, though, "but it was worth the time and the sleep lost, just the same."[3]

1910s

By 1912, 70 students had enrolled in the school. Early in the 1913-1914 school year, the students initiated a campaign to encourage prospective pupils to enroll at SHS. They strung a large canvas downtown to advertise the school and even made personal visits to enlist more youths. By February, the student population nearly reached the 100 mark. According to the SHS Annual, "when on February 27, it was discovered that the one-hundredth student was actually in attendance, the enthusiasm of the school knew no bounds and a holiday, to celebrate the occasion, was voted by the students and approved by the Board of Directors." The students then proceeded to parade the main streets of Springfield in the drizzling rain, led by a bugler and an array of banners and placards announcing the holiday.[2]

By all accounts, the student body of that year was a tightly knit group of friends who showed great enthusiasm for their school. Junior Walter Bailey, the President of the Student Body, wrote an essay in the 1914 Annual titled "Why Springfield High Is the School for Me." Bailey, who attended Eugene High School as a freshman, wrote, "I have nothing to say against the Purple and the White, but I have a great deal to say for the Blue and the White. I can say without exaggeration that I never met a more congenial and cordial group of students than I found in Springfield." Bailey notes the lack of cliques at his school and the general spirit of unity among the student body. "We are many in number but one in strength and purpose."[2]

The student body of that era was an industrious group whose activities included the first Annual (1914) and the first student periodical, The Headlight (November 14). Deterred by the lack of athletic facilities, students resorted to the Literary Society; with 60 members, it was by far the most popular club in the school. The literary Society initiated a debating team, which won "victory after victory..." although it did not win the regional championship at Villard Hall in Eugene. A typical Literary Society meeting would include roll call answered by famous quotations, a musical performance on the piano or violin, and a debate that dealt with a current school issue.

The students and the small faculty (six teachers in 1914) often indulged in parties and receptions, which were frequently sponsored in the home of a teacher. Individual classes usually threw their own receptions (the Freshmen party or the Senior party, for example), and could expect a friendly amount of rivalry from the other classes, whose members were fond of crashing parties and creating mischief.

On one occasion, Principal P.M. Stroud "entertained the seniors, juniors, and sophomores" at his house. The games of the evening included a "track meet," consisting of the broad jump and a relay race. Later that night, Manual Training Instructor Leslie McCoy performed as a hypnotist.[4]

The games were often disrupted when the freshmen were discovered lurking about the house. The upperclassmen would pause to chase them off then resume their activities. Later in the evening, however, someone sneaked up to the house, opened the kitchen window, and stole a "sack of sugar, a pail of syrup and a bottle of vinegar" that had been reserved for making taffy. The upperclassmen promptly accused the freshmen of the crime, and a great mock trial took place in the assembly hall of the school. In the end, the freshmen were found not guilty.[4]

At the head of all this activity were the charismatic figures of Walter Bailey, the popular leader with the polite smile, and Herbert Hansen, who must have received a great amount of mockery for his conspicuous ears. The two probably shared the sort of rivalry found between the classes: friendly but energetic. Both served as President of the Student Body (Baily in 1914 and Hansen in 1915) and both held the position of Editor-in-Chief of the new Annual (Hansen in 1914 and Bailey in 1915). On several occasions, both Bailey and Hansen filled the position of Literary Society President.[4]

The two would often find each other in disagreement over current issues. Bailey would generally support conservative notions while Hansen favored the more radical. In a Literary Society debate recorded in The Headlight, Bailey held that "the school board of District No. 19 are vested with power and are justified in... regulation the social life of the High School students." Hansen argued against him and lost the debate. (In the mock trial mentioned earlier, Bailey acted as prosecuting attorney while Hansen bravely agreed to defend the low-life freshmen; in that instance, Hansen emerged the victor.)

In the 1915 Annual, Senior Winona Platt predicted that Bailey would become a well-known evangelist and that Hansen would mature into the most famous orator of his day. In writing, Bailey preferred flowery language, while Hansen opted for a straight forward word choice. Hansen's "President's Report" seems remarkably to-the-point when compared to Bailey's "Why Springfield High Is the School for Me," which, after saying farewell to the departing seniors, comments, "this picture moistens the eye and causes the voice to grow husky, and I turn from it."[4]

Some of the class of 1915's activities reflect the blatant prejudices of the day. For instance, in an evening of dramatics sponsored by teachers, the students performed a 90 minute Minstrel Show wherein they blackened their faces with burnt cork and played such characters as Sambo. In it, Dinah, called "the Modern Joan of Arc," performed her famous speech "When Dey Enlisted Cull'ed Soldiers." The show concluded with "the roaring farce entitled Mr. Jackson's Servants, featuring Sambo, Dinah, Lizzy, Josey, and Lizah" as the servants. It is difficult to discover what became of those 100 students; more than likely, some died in the trenches of World War I. Others may be alive to this day.[4]

[1] The Millers: History of Springfield High School, editor Pat Albright, 8-9.

[2] Ibid., 12.

[3] Ibid., 24.

[4] Ibid., 13.

Administration

Springfield High School Principals

Flavius Roberts 1906-1907

H.C. Baughman 1907-1912

J.E. Torbert 1923-1924

L.E. Marschatt 1935-1936

Glen Martin 1936-1938

Cecil H. Davis 1938-1944

Owen Sabin 1944-1952

Warne Empey 1952-1956

Dale Parnell 1956-1961

Charles Smith 1961-1964

Ron Schiessl 1985-1994

Gene Heinle 1994-

Springfield High Head Coaches

Football Coaches

| Football Coaches | |||

| 1915- | Rex Putnam | 1921 | "Mack" McFadden |

| 1922 | Harold Barto | 1927 | Harold Finwick |

| 1933-37 | Marion Hall | 1937-1941 | Eldon Fix |

| 1943-1944 | John Young | 1946 | Bob Johnson |

| 1948 | John Young | 1950-1951 | Paul Evenson |

| 1952-1954 | George Zellick | 1958-1959 | Hal Whitbeck |

| 1962-1964 | Shelby Price | 1965 | Lee Insko |

| 1966 | JC Johnson | 1968-1970 | Jack Morris |

| 1971-1976 | Bob Harris | 1977-1979 | Vern Allers |

| 1979-1983 | Chuck Burns | 1984-1993 | Bob McKenzie |

| 1994-1998 | Ron Simmons | ||

| Baseball Coaches | |||

| 1914 | BH Smith | 1922 | "Mack" McFadden |

| 1923 | George Bliss | 1924 | Lester Wilcox |

| 1927 | Leonard Mayfield | 1934 | Kernal Buhler |

| 1935 | Robert Chatterton | 1937 | Harold Santee |

| 1938-1941 | Eldon Fix | 1942 | Paul Johnston |

| 1945-1953 | John Young | 1954 | Roger Wiley |

| 1955-1963 | John Young | 1964-1977 | Terry Maddox |

| 1977-1981 | Jim Fryback | 1982-95 | Bill Bowers |

| 1996-97 | Jason Hawkins | 1998 | Jim Fryback |