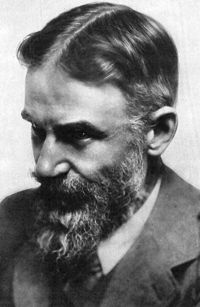

Bernard shaw

From Infocentral

George Bernard Shaw (born 26 July, 1856, Dublin, Ireland died November 2, 1950, Hertfordshire, England) was an Irish writer. Famed as a playwright, he wrote more than sixty plays. He was uniquely honoured by being awarded both a Nobel Prize (1925) for his contribution to literature and an Oscar (1938) for Pygmalion. He was a strong advocate for socialism and women's rights, a vegetarian and teetotaller, and a vocal critic of formal education. Shaw died in 1950 at the age of 94 as the result of injuries incurred by falling from a ladder while he was attempting to prune a tree.<ref>Biography eircom.net Accessed March 2007.</ref>

Contents |

Biography

Youth

George Bernard Shaw (1856 – 1950) was born in Dublin (Ireland), to George Carr Shaw (1814-1885), an unsuccessful grain merchant and sometime civil servant, and Lucinda Elizabeth Shaw, née Gurly (1830-1913), a professional singer. He had two sisters, Lucinda Frances (1853-1920), a singer of musical comedy and light opera, and Elinor Agnes (1854-1876); both died of tuberculosis.

Shaw briefly attended the Wesleyan Connexional School, a grammar school operated by the Methodist New Connexion, moved to a private school near Dalkey, transferred to Dublin's Central Model School and ended his formal education at the Dublin English Scientific and Commercial Day School. Boy and man, he was always bitterly opposed to schools and teachers, saying"Schools and schoolmasters, as we have them today, are not popular as places of education and teachers, but rather prisons and turnkeys in which children are kept to prevent them disturbing and chaperoning their parents."<ref>>(George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), Anglo-Irish playwright, critic. Letter, August 7, 1919, to Thomas Demetrius O'Bolger. "Biographers' Blunders Corrected," Sixteen Self Sketches, Constable (1949)</ref>He gave this attitude flesh and blood in the prologue of Cashel Byron's Profession, and underscored it in his Treatise on Parents and Children.

Just before Shaw’s sixteenth birthday (1872), his mother left home and followed her voice teacher, George Vandeleur Lee, to London. The daughters accompanied their mother, but Shaw remained in Dublin with his father while reluctantly completing his formal schooling, then working discontentedly as a clerk in an estate office.

Adulthood

In 1876 Shaw joined his mother’s London household. She, Vandeleur Lee, and his sister Lucy, provided him with a pound a week while he frequented public libraries and the British Museum reading room where he studied earnestly and began writing professionally. (He earned his allowance by ghost-writing Vandeleur Lee’s music column,which appeared in the London Hornet.) Between 1879 and 1883, thanks to a series of rejected novels, his literary earnings remained negligible. His situation improved after 1885, when he became able to support himself as an art and literary critic.

Influenced by his reading, he became a dedicated Socialist and an active member of the Fabian Society, a middle class organization, founded in 1884 to promote the gradual spread of socialism by peaceful means. In the course of his political activities he met Charlotte Payne-Townshend, an Irish heiress and fellow Fabian; they married in 1898. In 1906 the Shaws moved into a house in Ayot St Lawrence, a small village in Hertfordshire; it was to be their home for the remainder of their lives, although they also maintained a flat in London.

Accomplishments

Shaw's plays were first performed in the 1890s. By the end of the decade he was able to earn a living as a playwright. He wrote more than sixty plays and his output as novelist, critic, pamphleteer, essayist and private correspondent was prodigious. He is known to have written more than 250,000 letters.

He is the only person to have been awarded both a Nobel Prize (the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1925) and an Oscar (Academy Award for Writing Adapted Screenplay in 1938 for Pygmalion.[1])

Literary works

Criticism

As music, art and drama critic he wrote under the pseudonym "Corno di Bassetto" (Basset Horn) for the Wolverhampton Star and, as GBS, for Dramatic Review (1885-86), Our Corner (1885-86), and The Pall Mall Gazette (1885-88). From 1895 to 1898, Shaw was the drama critic for Frank Harris’ Saturday Review. His income as a critic made him self-supporting.

Shaw’s early journalism ranged from book reviews and art criticism to music columns (many of them defending the controversial work of the German composer Richard Wagner). The Perfect Wagnerite, printed in 1898, typifies Shaw’s views on Wagner. As drama critic for the Saturday Review, a post he held from 1895 to 1898, Shaw also championed the Norwegian dramatist Henrik Ibsen, about whom he had already written his influential The Quintessence of Ibsenism (1891). His music criticism has been collected in Shaw's Music (1981).<ref>Shaw's Music,Bodley Head Ltd, London, 1981. ISBN: 0370302494</ref>

Novels

All of the five unsuccessful novels written between 1879 and 1883, at the start of his career eventually were published. They were:

- Cashel Byron's Profession (London, The Modern Press, 1886)

- An Unsocial Socialist (London, Swan Sonnenschein, Lowrey & Co., 1887)

- Love Among the Artists (Chicago, Herbert S. Stone and Company, 1900, UK, 1914)

- The Irrational Knot, Being the Second Novel of his Nonage (revised, New York, Brentano’s, 1905)

- Immaturity (London, Constable, 1931) His first novel. Written in 1879, it was the last one to be printed.

The full texts of three of his novels are available online

Plays

Shaw started working on his first play, Widower's Houses, in 1885 in collaboration with critic William Archer, who supplied the structure. Archer decided that Shaw could not write a play (an opinion he apparently never changed), so the project was abandoned. Years later, Shaw tried again and, in 1892, completed the play without collaboration. Widower's Houses, which excoriated slumlords, was first performed at London's Royalty Theatre on December 9, 1892. Shaw would later call it one of his worst works, but he had found his medium.

His first significant financial success as a playwright came from Richard Mansfield's American production of The Devil's Disciple (1897). He went on to write 63 plays, most of them full-length. Often his plays succeeded in America and Germany before they did in London. Although major London productions of many of his earlier pieces were delayed for years, they are still being performed there. Examples include Mrs. Warren's Profession (1893), Arms and the Man (1894), Candida (1894) and You Never Can Tell (1895).

The humor in Shaw's writing was unmatched by any of his contemporaries excepting Oscar Wilde, and he is remembered for his comedy. However, his wittiness should not obscure his important role in revolutionizing British drama: In the Victorian Era, before Shaw's ascendancy, the London stage was regarded as a place for frothy, sentimental entertainment. He made it a forum for considering moral, political and economic issues. In doing this, he acknowledged his indebtedness to Henrick Ibsen, who was the pioneer of modern realistic drama.

As his experience and popularity increased, his plays became increasingly verbose, which did not detract from their success. These works, from what might be called the beginning of his "middle" period, include Caesar and Cleopatra (1898), Man and Superman (1903), Major Barbara (1905) and The Doctor's Dilemma (1906).

From 1904 to 1907, several of his plays had their London premieres in notable productions at the Court Theatre, managed by Harley Granville-Barker and J.E. Vedrenne. The first of his plays to be performed at the Court Theatre, John Bull's Other Island (1904), is not especially popular today, but it made his reputation in London when, during a command performance, King Edward VII laughed so hard he broke his chair.

By the 1910s, Shaw was a well-established playwright. New works such as Fanny's First Play (1911) and Pygmalion (1912)—on which My Fair Lady (1956) is based—had long runs in front of large London audiences. (Even though Oscar Straus's The Chocolate Soldier (1908)--an adaptation of Arms and the Man (1894)--was very popular, Shaw detested it and, for the rest of his life, forbade any musicalization of his work, including a potential Franz Lehar operetta based on Pygmalion. My Fair Lady was producible only after Shaw's demise.)

Shaw's outlook was changed by World War I, which he vigorously opposed, despite incurring outrage from the public as well as from many friends. His first full-length piece presented after the War, written mostly during it, was Heartbreak House (1919). A new Shaw was emerging--the wit remained, but his faith in humanity had dwindled. In the preface to Heartbreak House he said

"It is said that every people has the Government it deserves. It is more to the point that every Government has the electorate it deserves; for the orators of the front bench can edify or debauch an ignorant electorate at will. Thus our democracy moves in a vicious circle of reciprocal worthiness and unworthiness."

Shaw had previously supported gradual democratic change toward socialism, but now he arguably saw more hope in government by benign strong men. This would sometimes make him oblivious to the defects of dictators like Stalin, Hitler and Mussolini.

In 1921, Shaw completed Back to Methuselah, his "Metabiological Pentateuch." The massive, five-play work starts in the Garden of Eden and ends thousands of years in the future. Shaw proclaimed it a masterpiece, but many critics did not share that opinion.

His next play, Saint Joan (1923), is generally conceded to be one of his best. Shaw had long thought of writing about Joan of Arc, and her canonization supplied a strong incentive. The play was an international success, and is believed to have led to his Nobel Prize in Literature. He wrote plays for the rest of his life, but very few of them are as notable—or as often revived—as his earlier work.

The Apple Cart (1929) was probably his most popular work of this era. Later full-length plays like Too True to Be Good (1931), On the Rocks (play) (1933), The Millionairess (play) (1935), and Geneva (play) (1938) have been seen as marking a decline. His last significant play, In Good King Charles Golden Days has, according to St. John Ervine,<ref>St. John Ervine, Bernard Shaw: His Life, Work and Friends (London: Constable and Company Limited, 1949), p. 383</ref> passages that are equal to Shaw's major works. His last full-length work was Buoyant Billions (1946–48), written when he was in his nineties.

Shaw's published plays come with lengthy prefaces. These tend to be more about Shaw's opinions on the issues addressed by the plays than about the plays themselves. Often, his prefaces are longer than the play. For example, the Penguin Books edition of his one-act The Shewing-up Of Blanco Posnet (1909) has a 67-page preface for the 29-page playscript.

Political writing

His overriding motivation for writing was to further humanitarian and political agendas. To that end he mixed ideological points with witty dialogue, and his plays and lectures were very popular. Shaw himself was sometimes disappointed that the public often disregarded the prefaces and essays, and only enjoyed the plays as entertainment. His preface to Heartbreak House (1919) attributes the rejection to the need of post-World War I audiences for frivolities, after four long years of grim privation, more than to their inborn distaste of instruction.

His crusading nature led him to adopt and tenaciously hold a variety of causes, which he furthered with fierce intensity, heedless of all opposition or ridicule. For example, Commonsense about the War (1914) lays out Shaw's strong objections at the onset of World War I. His thoughts ran counter to public opinion and cost him dearly at the box-office, but he never compromised. He joined in the hysterical public attacks on vaccination against smallpox <ref>http://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/smallpox/sp_resistance.html</ref>, a dire disease that might have killed him when he contracted it in 1881.

As well as the plays and prefaces, Shaw wrote long political treatises, such as The Intelligent Woman's Guide to Socialism and Capitalism (1912),<ref>http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/shaw/works/guide1.htm</ref> a 495-page book detailing all aspects of socialistic theory as Shaw interpreted it. Exerpts were republished in 1928 as Socialism and Liberty<ref>http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/shaw/works/guide2.htm</ref>, and late in life he wrote another guide to political issues, Everbody's Political What's What.

Friends and correspondents

Shaw corresponded with an array of people, many of them well-known. His letters to and from Mrs. Patrick Campbell were adapted for the stage by Jerome Kilty as Dear Liar: A Comedy of Letters; as was his correspondence with the poet Lord Alfred 'Bosie' Douglas (the intimate friend of Oscar Wilde), into the drama Bernard and Bosie: A Most Unlikely Friendship by Anthony Wynn. His letters to the prominent actress, Ellen Terry,<ref> Ellen Terry and Bernard Shaw : A Correspondence / The Shaw - Terry Letters : A Romantic Correspondence, (Christopher St. John, Editor)</ref>, to the boxer Gene Tunney,<ref> (Collier’s Magazine 23 June 1951)</ref> and to H.G. Wells, <ref>Bernard Shaw and H.G. Wells (Selected Correspondence of Bernard Shaw) (J. Percy Smith, Editor)</ref> have also been published.. Eventually the volume of his correspondence became insupportable, as can be inferred from apologetic letters written by assistants.

Shaw campaigned against the executions of the rebel leaders of the Easter Rising, and he became a personal friend of the Cork-born IRA leader Michael Collins, whom he invited to his home for dinner while Collins was negotiating the Anglo-Irish Treaty with Lloyd George in London. After Collins's assassination in 1922, Shaw sent a personal message of condolence to one of Collins's sisters.

Shaw had an enduring friendship with G. K. Chesterton, the Roman Catholic-convert British writer. The e-text of their famed debate, Shaw V. Chesterton is available, as is a book, Shaw V. Chesterton, a debate between George Bernard Shaw and G.K. Chesterton (2000 Third Way Publications Ltd. [ISBN 0-9535077-7-7])

Another great friend was the composer Edward Elgar. The latter dedicated one of his late works, Severn Suite, to Shaw; and Shaw exerted himself (eventually with success) to persuade the BBC to commission from Elgar a third symphony, though this piece remained incomplete at Elgar's death.

Shaw's correspondence with the motion picture producer Gabriel Pascal, who was the first to successfully bring Shaw's plays to the screen and who later tried to put into motion a musical adaptation of Pygmalion, but died before he could realize it, is published in a book titled Bernard Shaw and Gabriel Pascal (ISBN 0-8020-3002-5).

A stage play based on a book by Hugh Whitemore, The Best of Friends, provides a window on the friendships of Dame Laurentia McLachlan, OSB (late Abbess of Stanbrook) with Sir Sydney Cockerell and Shaw through adaptations from their letters and writings.

Socialism and political beliefs

In a letter to Henry James dated 17 January, 1909 Shaw said:

“I, as a Socialist, have had to preach, as much as anyone, the enormous power of the environment. We can change it; we must change it; there is absolutely no other sense in life than the task of changing it. What is the use of writing plays, what is the use of writing anything, if there is not a will which finally moulds chaos itself into a race of gods.”

Shaw maintained that each social class worked to serve its own ends, and that those in the upper echelons had won the struggle. He believed the working class had failed to promote its interests effectively, which made him highly critical of the democratic system of his time. Shaw's writing, as evinced in plays like Major Barbara and Pygmalion, has class struggle as an underlying theme. Notwithstanding that, Shaw was not a Marxist in the traditional sense, and abhorred the aggressiveness of Trade Unionism.

In 1882 Henry George's views on land nationalization gave depth and direction to Shaw’s political convictions. Shortly thereafter he applied to join the Social Democratic Federation led by H. M. Hyndman who introduced him to the works of Karl Marx. However, the newly-formed Fabian Society conformed more closely to his views, so he joined it instead, in 1884. He was an active Fabian, writing a number of their pamphlets, and supplying money to set up the independent socialist journal The New Age. He argued that owning property was a form of theft and campaigned for an equitable distribution of land and capital. He was involved with the formation of the Labour Party. A clear statement of his position can be found in The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism, Capitalism, Sovietism, and Fascism, also known as The Intelligent Woman's Guide to Socialism and Capitalism. Having visited the USSR in 1930s and met Stalin, Shaw became an ardent supporter of the Stalinist USSR. He declared that all the stories of a famine were slander after a carefully managed short tour of the country (Stalin privately disparaged him). Having been asked why he didn't want to stay permanently in the Soviet 'earthly paradise', Shaw ironically remarked that England was a 'hell' but of course he was a small devil himself. He wrote a somewhat ironic defense of Stalin's espousal of Lysenkoism, in a letter to the 1946 Labour Monthly. He also "simply did not believe" that the Holocaust had happened.<ref>Baker, Stuart E., Bernard Shaw's Remarkable Religion: A Faith That Fits the Facts, p. 177. University Press of Florida: Gainesville, Florida: 2002.</ref>

Vegetarianism

G.B. Shaw became a vegetarian while he was twenty-five, after hearing a lecture by H. F. Lester <ref>Archibald Henderson, George Bernard Shaw: Man of the Century (N.Y.: Appleton-Century-Crofts Inc., 1956), 777</ref>

In 1901, remembering the experience, he said "I was a cannibal for twenty-five years. For the rest I have been a vegetarian." <ref>Who I Am, and What I Think, Sixteen Self Sketches,' Constable (1949)</ref> As a staunch vegetarian, he was firmly anti-vivisectionist and antagonistic to cruel sports for the balance of his life. The belief in the immorality of killing animals for food was one of the Fabian causes near his heart and is frequently a topic in his plays and prefaces. His position, succinctly stated, was "A man of my spiritual intensity does not eat corpses."<ref>Hesketh Pearson, Bernard Shaw: His Life and Personality, ch. 9 ((Atheneum Press, 1963)</ref>

The following was taken from the archives of The Vegetarian Society UK:<ref>http://www.ivu.org/history/shaw/index.html</ref>

- ...the big story of the July issue of The Vegetarian Messenger was the tribute to George Bernard Shaw, celebrating his 90th birthday on the 26th of that month. He had, at that time, been a vegetarian for 66 years and was commended as one of the great thinkers and dramatists of his era. "No writer since Shakespearean times has produced such a wealth of dramatic literature, so superb in expression, so deep in thought and with such dramatic possibilities as Shaw."

Shaw's legacy

When his life ended, Shaw was a world figure and a household name in Great Britain. His ironic wit endowed English with the adjective "Shavian" to describe to such clever observations as "[Dancing is] a perpendicular expression of a horizontal desire."

Concerned about the vagaries of English spelling, he willed a portion of his wealth (probated at £367,233 13s <ref>Oxford Dictionary of National biography</ref>) to fund the creation of a new phonemic alphabet for the English language.When he died he did not leave much money, so no effort was made to start the project. However, his estate began to earn significant royalties from the rights to Pygmalion when My Fair Lady, a musical adapted from the play by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe, became a hit. It then became clear that the will was badly worded and the Public Trusteefound grounds to challenge it. In the end an out-of-court settlement granted only a small portion of the money for promoting the new alphabet, which is now called the Shavian alphabet. The National Gallery of Ireland, RADA and the British Museum all received substantial bequests.

His home, now called Shaw's Corner, in the small village of Ayot St Lawrence, Hertfordshire is now a National Trust property, open to the public.

The Shaw Theatre, Euston Road, London was opened in 1971 and named in his honour.

The Shaw Festival, an annual theater festival in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, began as an eight week run of Don Juan in Hell (as the long third act dream sequence of Man And Superman is called when staged alone) and Candida in 1962 and has grown into an annual festival with over 800 performances a year, dedicated to producing the works of Shaw and his contemporaries.

Works available online

Novels

- Cashel Byron's Profession (London, the Modern Press, 1886)[2]

- An Unsocial Socialist (London, Swan Sonnenschein, Lowrey & Co., 1887)[3]

- The Irrational Knot (revised, New York, Brentano’s, 1905)Immaturity (London, Constable, 1931)[4]

Drama

Template:Col-begin Template:Col-2

- Plays Unpleasant (published 1898)

- Widowers' Houses(1892)[[5]

- The Philanderer (1893)[6]

- Mrs Warren's Profession (1893)[7]

- Plays Pleasant (published 1898):

- Arms and the Man (1894)[8]

- Candida (1894)[9]

- The Man of Destiny (1895)[10]

- You Never Can Tell (1897)[11]

- Three Plays for Puritans (published 1901):

- The Devil's Disciple (1897)[12]

- Caesar and Cleopatra (1898)[13]

- Captain Brassbound's Conversion (1899)[14]

- The Admirable Bashville (1901)[15]

- Man and Superman (1902-03)[16]

- John Bull's Other Island (1904)[17]

- How He Lied to Her Husband (1904)[18]

- Major Barbara (1905)[19]

- The Doctor's Dilemma (1906)[20]

- Getting Married (1908)[21]

- The Glimpse of Reality (1909)[22]

- Misalliance (1910)[23]

- Annajanska, the Bolshevik Empress(1917)[24]

- Dark Lady of the Sonnets (1910)[25]

- Alternate source for "Dark Lady" (1910) [26]

- Fanny's First Play (1911)[27]

- Androcles and the Lion 1912)[28]

- Pygmalion(1912-13)[29]

- The Inca of Perusalem (1915) [30]

- O'Flaherty VC (1915)[31]

- Heartbreak House(1919)[32]

- Back to Methuselah(1921)[33]

- In the Beginning

- The Gospel of the Brothers Barnabas

- The Thing Happens

- Tragedy of an Elderly Gentleman

- As Far as Thought Can Reach

- Saint Joan (1923)[34]

- The Apple Cart (1929)[35]

- Too True To Be Good (1931)[36]

- On the Rocks(1933)[37]

- The Six of Calais(1934)[38]

- The Simpleton of the Unexpected Isles(1934)[39]

- The Shewing Up of Blanco Posnet (1909)[40]

- The Millionairess (1936)[41]

- Geneva(1938)[42]

- In Good King Charles' Golden Days (1939)[43]

- Buoyant Billions (1947)[44]

- Shakes versus Shav (1949)[45]

Essays

- Quintessence of Ibsenism (1891)[46]

- The Perfect Wagnerite, Commentary on the Ring (1898}[47]

- Preface to Major Barbara {1905) [48]

- How to Write a Popular Play (1909) [49]

- Treatise on Parents and Children (1910)[50]

- Commonsense about the War(1914)[51]

- The Intelligent Woman's Guide to Socialism and Capitalism (1928)[52]

- Everybody's Political What's What?(Constable,1944) [53]

Debate

- Shaw V. Chesterton, a debate between George Bernard Shaw and G.K. Chesterton 2000 Third Way Publications Ltd. ISBN 0-9535077-7-7[54]

References and footnotes

Further reading

- Ohmann, Richard M., "Shaw: The Style and the Man", Wesleyan University Press, 1962

- Holroyd, Michael, Bernard Shaw: The One-Volume Definitive Edition, Random House, 1998

See also

External links

- The Nobel Prize Bio on Shaw

- "Excerpt from Caesar and Cleopatra" Creative Commons audio recording.

- Dan H. Laurence/Shaw Collection in the University of Guelph Library, Archival and Special Collections, holds more than 3,000 items related to his writings and career.

- The Shaw Society

- The Bernard Shaw Society, New York

- The Bernard Shaw Pub, South Richmond Street, Dublin 2, Ireland

- Shaw sayings in Wikiquote

- This includes a year-by-year chronology of Shaw's life and works

- WorldCat Identities page for 'Shaw, Bernard 1856-1950'

Template:Nobel Prize in Literature Laureates 1901-1925 Template:Persondata