Datarium - Dracomicon

From Conworld

//This article is mostly from Draconomicon. Wizards of the Coast. This is used largely for reference and inspirational purposes, NOT to be taken as our original work

Dragons are creatures of myth, often described as the first sentient race to appear on a world, with life spans that stretch over hundreds of years. They symbolize the world itself and embody its history, and the oldest dragons are repositories of vast knowledge and ancient secrets. This aspect of dragons makes them much more than just a challenging combat encounter: They are sages and oracles, fonts of wisdom and prophets of things to come. Their very appearance can be an omen of good or ill fortune.

Any attempt to describe them as little more than glorified lizards with wings and breath weapons is a disservice. Dragons are, by their very nature, epic forces in the world. Their actions, their schemes, even their dreams are felt throughout the world. From a wyrmling raiding herds of sheep to the mighty Ashardalon feasting on preincarnate souls, dragons do things that matter, whether on a small local scale or in the cosmic big picture. They are the embodiment of fantasy itself.

Dragons are rapacious, arrogant, and deadly — but they are also majestic, awesome, and magnificent.

Contents |

All about Dragons

A wealth of material, from bard’s tales and ponderous tomes alike, has been recorded about dragons. Unfortunately for adventurers planning to confront a dragon, most of that information is wrong. The opening chapter of this book presents the truth about dragons—their types, habits, physiology, and worldview.

The Dragon's Body

At first glance, a true dragon resembles a reptile. It has a muscular body, a long, thick neck, a horned or frilled head with a toothy mouth, and a sinuous tail. The creature walks on four powerful legs with clawed feet, and it flies using its vast, batlike wings. Heavy scales cover a dragon from the tip of its tail to end of its snout. As you’ll see from the details to come, however, that first glance doesn’t begin to tell the whole story about the nature of dragons.

External Anatomy

Despite its scales and wings, a dragon’s body has features that seem more feline than reptilian. Like a cat’s eye, a dragon’s eye has a comparatively large iris with a vertical pupil. This arrangement allows the pupil to open extremely wide and admit much more light than a human eye can.

Eyes

The sclera, or “white,” of a dragon’s eye is often yellow, gold, green, orange, red, or silver, with an iris of a darker, contrasting color.

To a casual observer, a dragon’s pupils always look like vertical slits. If one were to look very closely into a dragon’s eye, however, one could see a second iris and pupil within the first. The dragon can shift and rotate this inner aperture up to 90 degrees, so that the inner pupil can overlay the outer one or lie at a right angle to it. This ocular structure gives a dragon extremely accurate depth perception and focusing ability no matter how much or how little light is available.

A dragon’s eye is protected by a leathery outer eyelid and three smooth inner eyelids, or nictitating membranes. The innermost membrane is crystal clear and serves to protect the eye from damage while the dragon flies, fights, swims, or burrows with its eyes open. The other two eyelids mainly serve to keep the inner membrane and the surface of the eye clean. They are thicker than the innermost membrane and less clear. A dragon can use these inner lids to protect its eyes from sudden flashes of bright light. A dragon’s eyes glow in the dark, but the dragon can hide the glow by closing one or more of its inner eyelids; doing this does not affect its vision.

Inside the Dragon’s Eye

Most scholars remain unaware of how complex and unusual a dragon’s eye really is. In addition to its four layers of eyelids and its double pupil, a dragon’s eye also has a double lens. The outer lens (1) is much the same as any other creature’s in form and function. The inner lens (2), however, is a mass of transparent muscle fibers that can polarize incoming light. The inner lens also serves to magnify what the dragon sees, and helps account for the dragon’s superior longdistance vision. A dragon’s retinas (3) are packed with receptors for both color and black-and-white vision. Behind the retina lies the tapetum lucidum (4), a reflective layer that helps the dragon see in dim light. A dragon literally sees light twice, once when it strikes the retina and again when it is reflected back. It is the tapetum lucidum that makes a dragon’s eyes seem to glow in the dark.

Ears

A dragon’s ears often prove indistinguishable from the frills that frame its head, especially when the dragon is at rest. The ears of an an active dragon, however, constantly twitch and swivel as the dragon tracks sounds. Not all dragons have external ears; burrowing and aquatic dragons usually have simple ear holes protected by an overhanging fringe.

Mouth

A dragon’s mouth features powerful jaws, a forked tongue, and sharp teeth. The exact number and size of a dragon’s teeth depend on the dragon’s age, habitat, and diet; however, a dragon’s array of teeth usually includes four well-developed fangs (two upper, two lower) that curve slightly inward and have cutting edges on both the inner and outer surfaces. A dragon uses its fangs to impale and kill prey, and they serve as the dragon’s primary weapons.

Immediately in front of the fangs in each jaw lie the dragon’s incisors, which are oval in cross-section and have serrated edges at the top. When a dragon bites down on large prey, these teeth cut out a semicircle of flesh. Behind the fangs in each jaw, a dragon has a row of peglike molars that help it grip prey. A dragon is not well equipped for chewing, and it typically tears prey into chunks small enough to gulp down. A dragon can create a sawing motion with its incisors by wiggling its lower jaw and shaking its head from side to side, allowing the incisors to quickly shear through flesh and bone.

Many dragons learn to seize prey and literally shake it to death. Other dragons have mastered the technique of grabbing prey and swallowing it whole.

Some dragon hunters boast that they can hold a dragon’s mouth closed, preventing the creature from biting. It is true that a dragon applies more force when closing its jaws than it does when opening them; however, holding a dragon’s mouth closed still requires prodigious strength. Even if an foe were to succeed in clamping its jaws shut, the dragon is likely to throw off the opponent with one flick of its head, claw its attacker to ribbons, or both.

Spines, frills and other projections

The spines, frills, and other projections that adorn a dragon’s head make the creature look fearsome, and that is their main function.

A dragon’s horn is a keratinous projection growing directly from the dragon’s skull. A dragon with horns that point backward can use the horns for grooming, and they also help protect the dragon’s upper neck in combat. Horns projecting from the sides of a dragon’s head help protect the head.

A dragon’s spines are keratinous, but softer and more flexible than its horns. The spines are imbedded in the dragon’s skin and anchored to the skeleton by ligaments. Most spines are located along the dragon’s back and tail. Unlike horns, spines are mobile, with a range of motion that varies with the kind of dragon and the spines’ location on the dragon’s body. The spines along a dragon’s back, for example, can only be raised or lowered, whereas the spines supporting a dragon’s ears can be moved many different ways.

The frills on a dragon’s back and tail help keep the dragon stable when flying or swimming.

Limbs

To a scholar who knows something about the natural world, a dragon’s powerful legs are decidedly nonreptilian, despite their scaly coverings. A dragon’s legs are positioned more or less directly under its body, in the manner of mammals. (Most reptiles’ legs tend to splay out to the sides, offering much less support and mobility than a dragon or mammal enjoys.)

A dragon’s four feet resemble those of a great bird. Each foot has three or four clawed toes facing forward (the number varies, even among dragons of the same kind), plus an additional toe, also with a claw, set farther back on the foot and facing slightly inward toward the dragon’s body, like a human’s thumb.

Although a dragon’s front feet are not truly prehensile, a dragon can grasp objects with its front feet, provided they are not too small. This grip is not precise enough for tool use, writing, or wielding a weapon, but a dragon can hold and carry objects. A dragon also is capable of wielding magical devices, such as wands, and can complete somatic components required for the spells it can cast (see Spellcasting, below). Some dragons are adroit enough to seize prey in their front claws and carry it aloft.

A dragon can use the “thumbs” on its rear feet to grasp as well, but the grip is less precise than that of the front feet.

Skin

A dragon’s skin resembles crocodile hide—tough, leathery. and thick. Unlike a crocodile, however, a dragon has hundreds of hard, durable scales covering its body. A dragon’s scales are keratinous, like its spines. Unlike the spines, however, a dragon’s scales are not attached to its skeleton, and the dragon cannot make them move. The scales are much harder and less flexible than the spines, with a resistance to blows that exceeds that of steel.

A dragon’s largest scales are attached to its hide along one edge and overlap their neighbors like shingles on a roof or the articulated plates in a suit of armor. These scales cover the dragon’s neck, underbelly, toes, and tail. As the dragon moves its body, the scales tend to shift as the skin and muscle under them moves, and the scales’ free ends sometimes rise up slightly. This phenomenon has led some observers to mistakenly conclude that a dragon can raise and lower its scales in the same manner as a bird fluffing its feathers.

The majority of a dragon’s scales are smaller and attached to the skin near their centers. These scales interlock with neighboring scales, giving the surface of the body a pebbly texture. The scales are large enough to form a continuous layer of natural armor over the body even when it stretches or bulges to its greatest extent. When the body relaxes or contracts, the skin under the scales tends to fold and wrinkle, though the interlocking scales give the body a fairly smooth look.

A dragon’s scales grow throughout its lifetime, albeit very slowly. Unlike most other scaled creatures, a dragon neither sheds its skin nor sheds individual scales. Instead, its individual scales grow larger, and it also grows new scales as its body gets bigger. Over the years, a scale may weather and crack near the edges, but its slow growth usually proves sufficient to replace any portion that breaks off. Dragons occasionally lose scales, especially if they become badly damaged. Old scales often litter the floors of long-occupied dragon lairs.

When a dragon loses a scale, it usually grows a new one in its place. The new scale tends to be smaller than its neighbors and usually thinner and weaker as well. This phenomenon is what gives rise to bards’ tales about chinks in a dragon’s armor. These tales are true as far as they go, but one new scale on a dragon’s massive body seldom leaves the dragon particularly vulnerable to attack.

Tail and Wings

A dragon’s long, muscular tail serves mainly as a rudder in flight. A dragon also uses its tail for propulsion when swimming, and as a weapon.

A dragon’s wings consist of a membrane of scaleless hide stretched over a framework of strong but lightweight bones. Immensely powerful muscles in the dragon’s chest provide power for flight.

Most dragons have wings that resemble bat wings, with a relatively short supporting alar limb, ending in a vestigial claw that juts forward. Most of the wing area comes from a membrane stretched over elongated “fingers” of bone (the alar phalanges; see Skeleton, below), which stretch far beyond the alar limb.

Some kinds of dragons have wings that run the lengths of their bodies, something like the “wings” of manta rays. This sort of wing also has an alar limb with phalanges supporting the forward third of the wing, but the remainder of the wing is supported by modified frill spines that have only a limited range of motion and muscular control.

Internal Anatomy

As you’ll see from the following section, a dragon’s resemblance to a reptile is literally only skin deep. Refer to the accompanying illustrations as you read on.

Skeleton

Although complete dragon skeletons are hard to come by, most scholars agree that a little more than 500 bones comprise a dragon’s skeleton, compared to slightly more than 200 bones in a human skeleton. The bones in a dragon’s wings and spine account for most of the difference. Dragon bones are immensely strong, yet exceptionally light. In cross-section they look hollow, with thick walls made up of concentric circles of small chambers staggered like brickwork. Layers of sturdy connective tissue and blood vessels run between the layers.

The accompanying diagram shows a dragon skeleton in detail. Significant parts of the skeleton are briefly discussed below.

The keel, or sternum (1), serves as an anchor for the dragon’s flight muscles. The scapula draconis (2) supports the wing. The metacarpis draconis (3) and alar phalanges (4) in each wing support most of the wing’s flight surface. In some dragons, the ulna draconic (5) has an extension called the alar olecranon (6) that lends extra support to the wing.

The thirteenth cervical vertebra (7) marks the base of a dragon’s neck. Every true dragon, no matter how large or small, has exactly 13 cervical vertebrae, 12 thoracic vertebrae, 7 lumbar vertebrae, and 36 caudal vertebrae.

Major Internal Organs

The insides of a dragon have several noteworthy features, all of which contribute to the dragon’s unique capabilities.

A dragon’s eyes (1) are slightly larger than they appear from the outside. The bulk of the eye remains buried inside the skull, with only a small portion of the whole exposed when a dragon opens its eyes. The eye’s extra size helps improve the dragon’s ability to see at a distance.

The eye’s spherical shape allows the dragon to move the eye through a wide arc, helping to expand its field of vision. A dragon’s brain (2) is exceptionally large, even for such a big creature, and it continues to grow as the dragon grows.

It has highly developed sensory centers with specialized lobes that connect directly to the eyes, ears, and nasal passages. The brain also has large areas dedicated to memory and reasoning.

The larynx (3) contains numerous well-developed vocal folds that give a dragon tremendous control over the tone and pitch of its voice. A dragon’s voice can be as shrill as a crow’s or as deep as a giant’s. Some scholars, noting that the Draconic language contains many harsh sounds and sibilants, conclude that a dragon’s vocal capacity is limited, but this is not so. Dragons speak a strident language because it suits them to do so.

The trachea (4) connects the larynx to the lungs. It is the dragon’s conduit for respiration and also for its breath weapon.

A dragon’s vast lungs (5) fill much of its chest cavity. The lung structure resembles that of an avian, which can extract oxygen both on inhalation and exhalation. In addition to being the organs for respiration, a dragon’s breath weapon is generated in its lungs from secretions produced by the draconis fundamentum (see below). A dragon’s mighty heart (6) has four chambers, just like a mammal’s heart.

The draconis fundamentum (7) is a gland possessed only by true dragons. Attached to the heart, it is the center of elemental activity inside the dragon’s body. All blood flowing from the heart passes through this organ before going to the body. The draconis fundamentum charges the lungs with power for a dragon’s breath weapon and also plays a major role in the dragon’s highly efficient metabolism, which converts the vast majority of whatever the creature consumes into usable energy. Blood vessels, nerves, and ducts run directly from the draconis fundamentum to the dragon’s flight muscles, charging them with enormous energy, and also to the lungs and the gizzard. A dragon digests its food through a combination of powerful muscular action and elemental force. The interior of the gizzard (8) is lined with bony plates that grind up chunks of food, and the entire organ is charged with the same elemental energy that the dragon uses for its breath weapon.

Musculature

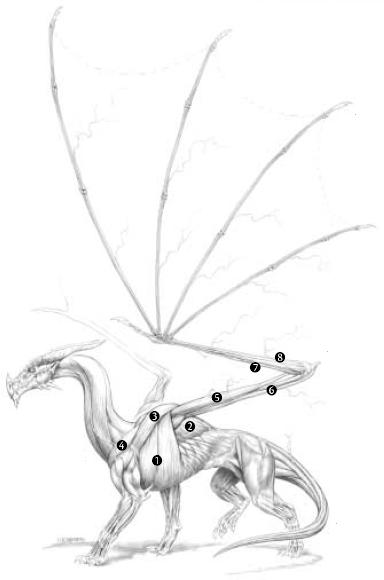

Intact dragon carcasses are even more rare than intact dragon skeletons, making any catalog of a dragon’s muscles unreliable at best. Given the number of bones in a dragon skeleton, however, a dragon’s muscles must number in the thousands. Overall, a dragon’s musculature resembles that of a great cat, but with much larger muscles in the chest, neck, and tail. The illustration on page 10 identifies the major muscle groups in a dragon’s body.

Of most interest to scholars are the muscles involved in flight. These muscles can exert tremendous force and consume equally tremendous amounts of energy (which the draconis fundamentum supplies). The flight muscles are located in the chest and in the wings themselves. The alar pectoral (1) is the main flight muscle and is used on the wing’s downstroke. The alar lattisimus dorsai (2) draws the wing up and back. The alar deltoid (3) and alar cleidomastoid (4) draw the wings up and forward.

The muscles of the wings serve mainly to control the wing’s shape, which in turn helps the dragon maneuver in the air. The alar tricep (5) and alar bicep (6) fold and unfold the wings. The alar carpi ulnaris (7) and alar carpi radialus (8) allow the wings to warp and twist.

Dragon Physiology

Scholars disagree on some key aspects of dragon life, but dragons themselves have few doubts.

Metabolism

Laypeople, and some scholars, are fond of the terms “coldblooded” and “warm-blooded” to describe ectothermic and endothermic creatures, respectively.

An ectothermic creature lacks the ability to produce its own heat and must depend on its environment for warmth. Most ectothermic creatures seldom actually have cold blood, because they are able to find environmental heat to warm their bodies.

An endothermic creature doesn’t necessarily have warm blood. What it has is a body temperature that remains more or less steady no matter how hot or cold its surroundings become.

All true dragons are endothermic. Given their elemental nature, they could hardly be otherwise. A dragon’s body temperature depends on its kind and sometimes on its age. Dragons that use fire have the highest body temperatures, and dragons that use cold have the lowest. Acid- and electricity-using dragons have body temperatures that fall between the two extremes, with acid-users tending to have cooler bodies than electricity-users. Fire-using dragons literally become hotter with age. Likewise, cold-using dragons become colder as they age. Acid- and electricity-using dragons have about the same body temperature throughout their lives, with younger and smaller dragons having slightly higher temperatures than older and larger ones.

Unlike most endothermic creatures, dragons have no obvious way to shed excess body heat. They do not sweat, nor do they pant. Instead, the draconis fundamentum extracts heat from the bloodstream and stores the energy. In a sense, then, a dragon can be considered ectothermic (because it can use environmental heat). However, when a dragon is deprived of an external heat source, its metabolism and activity level do not change. Unlike a truly ectothermic creature, a dragon can generate its own body heat and is not slowed orforced into hibernation by exposure to cold.

Diet

Dragons are carnivores and top predators, though in practice they are omnivorous and eat almost anything if necessary. A dragon can literally eat rock or dirt and survive. Some dragons, particularly the metallic ones, subsist primarily on inorganic fare. Such dining habits, however, are cultural in origin.

Unfortunately for a dragon’s neighbors, the difference between how much a dragon must eat and how much it is able to eat is vast. Most dragons can easily consume half their own weight in meat every day, and many gladly do so if sufficient prey is available. Even after habitual gorging, a dragon seldom gets fat. Instead, it converts its food into elemental energy and stores it for later use. Much of this stored energy is expended on breath weapons and on the numerous growth spurts (see below) that a dragon experiences throughout its life.

Dragon Life Cycles

Barring some misfortune, a dragon can expect to live in good health for 1,200 years, possibly even a great deal longer, depending on its general fitness. All dragons, however, start out as humble eggs and progress through twelve distinct life stages, each marked by new developments in the dragon’s body, mind, or behavior.

Eggs

Dragon eggs vary in size depending on the kind of dragon. They are generally the same color as the dragon that laid them and the have the same energy immunities as the dragon that laid them (for example, black dragon eggs are black or dark gray and impervious to acid). A dragon egg has an elongated ovoid shape and a hard, stony shell.

A female dragon can produce eggs beginning at her young adult stage and remains fertile though the very old stage. Males are capable of fertilizing eggs beginning at the young adult stage and remain fertile through the wyrm stage.

The eggs are fertilized inside the female’s body and are ready for laying about a quarter of the way through the incubation period, as shown on the table below. The numbers given on the table are approximate; actual periods can vary by as much as 10 days either way.

Laying eggs

Dragon eggs are laid in clutches of two to five as often as once a year. Ovulation begins with mating, and a female dragon can produce eggs much less often, if she wishes, simply by not mating. Mating and egg laying can happen in almost any season of the year.

Most dragon eggs are laid in a nest within the female’s lair, where the parent or parents can guard and tend them. A typical nest consists of a pit or mound, with the eggs completely buried in loose material such as sand or leaves. A dragon egg’s ovoid shape gives it great resistance to pressure, and the female can walk, fight, or sleep atop the nest without fear of breaking her eggs.

Dragons sometimes leave their eggs untended. In such cases, the female takes great care to keep the nest hidden. She or her mate (or both of them) may visit the area containing the nest periodically, but they take care not to approach the nest too closely unless some danger threatens the eggs.

Incubating Dragon Eggs

Once laid, a dragon egg requires suitable incubation conditions if it is to hatch. The basic requirements depend on the kind of dragon, as described below. The embryonic wyrmling inside a dragon egg can survive under inadequate incubation conditions, but not for long.

An embryonic wyrmling inside a dragon egg becomes sentient as it enters the final quarter of the incubation period.

Dragon egg incubation conditions are as follows:

- Black: The egg must be immersed in acid very strong, or sunk in a swamp, bog, or marsh.

- Blue: For half of each day, the egg must be kept in a temperature of 90°F to 120°F, followed by a half day at 40°F to 60°F.

- Brass: The egg must be kept in an open flame or in a temperature of at least 140°F.

- Bronze: The egg must be immersed in a sea or ocean or someplace where tidewaters flow over it at least twice a day.

- Copper: The egg must be immersed in very strong acid, or packed in cool sand or clay (40°F to 60°F).

- Gold: The egg must be kept in an open flame or in a temperature of at least 140°F.

- Green: The egg must be immersed in very strong acid, or buried in leaves moistened with rainwater.

- Red: The egg must be kept in an open flame or in a temperature of at least 140°F.

- Silver: The egg must be buried in snow, encased in ice, or kept in a temperature below 0°F.

- White: The egg must be buried in snow, encased in ice, or kept in a temperature below 0°F.

Hatching Dragon Eggs

When a dragon egg finishes incubating, the wyrmling inside must break out of the egg. If the parents are nearby, they often assist by gently tapping on the eggshell. Otherwise, the wyrmling must break out on its own, a process that usually takes no more than a minute or two once the wyrmling begins trying to escape the egg. All the eggs in a clutch hatch at about the same time.

Properly tended and incubated dragon eggs have practically a 100% hatching rate. Eggs that have been disturbed, and particularly eggs that have been removed from a nest and incubated artificially, may be much less likely to produce live wyrmlings.

Opening an egg before the final quarter of the incubation period causes the wyrmling inside to die. If the egg is opened during the final quarter of the incubation period, the wyrmling can make a check to survive, but if successful it takes nonlethal damage equal to its current hit points. This damage cannot be healed until the wyrmling’s normal incubation period passes, and the wyrmling remains staggered for the entire period. During this period, a prematurely hatched wyrmling must be tended in the same manner as an unhatched egg in order to survive.

Wyrmling (Age 0-5 years)

A wyrmling emerges from its egg fully formed and ready to face life. From the tip of its nose to the end of its tail, it is about twice as long as the egg that held it.

A newly hatched dragon emerges from its egg cramped and sodden. After about an hour, it is ready to fly, fight, and reason. It inherits a considerable body of practical knowledge from its parents, though such inherent knowledge often lies buried in the wyrmling’s memory, unnoticed and unused until it is needed.

Compared to older dragons, a wyrmling seems a little awkward. Its head and feet seem slightly oversized, and its wings and tail are proportionately smaller than they are in adults.

If a parent is present at the wyrmling’s hatching, the youngster has a protector and will probably enjoy a secure existence for the first decades of its life. If not, the wyrmling faces a struggle for survival.

Whether raised by another dragon or left to fend for itself, the wyrmling’s first order of business is learning to be a dragon, which includes securing food, finding a lair, and understanding its own abilities (usually in that order).

A newly hatched wyrmling almost immediately searches for food. The first meal for a wyrmling left to fend for itself is often the shell from its egg. This practice not only assures the youngster a good dose of vital minerals, but also provides an alternative to attacking and consuming its nestmates. Wyrmlings reared by parents are often offered some tidbit that the variety favors. For example, copper dragons provide their offspring with monstrous centipedes or scorpions. In many cases this meal is in the form of living prey, and the wyrmling gets its first hunting lesson along with its first meal.

With its hunger satisfied, the wyrmling’s next task is securing a lair. The dragon looks for some hidden and defensible cave, nook, or cranny where it can rest, hide, and begin storing treasure. Even a wyrmling under the care of a parent finds a section of the parent’s lair to call its own.

Once it feels secure in its lair and reasonably sure of its food supply, the wyrmling settles down to hone its inherent abilities.

It usually does so by testing itself in any way it can. It tussles with its nestmates, seeks out dangerous creatures to fight, and spends long hours in meditation. If a parent is present, the wyrmling receives instruction on draconic matters and the chance to accompany the parent during its daily activities. Wyrmlings on their own sometimes seek out older dragons of the same kind as mentors. Among good dragons, such relationships tend to be casual and often last for decades (a fairly short period by dragon standards). The youngster visits the older dragon periodically (monthly, perhaps weekly) for advice and information. Evil dragons, too, often counsel wyrmlings that are not their offspring—evil dragons lack any sense of altruism, but usually understand the role of youth in perpetuating the species.

No matter what kinds of dragons are involved, such mentor-apprentice relationships require the younger dragon to show the utmost respect and deference to the older dragon, and to bring the mentor gifts of food, information, and treasure. Should the older dragon ever come to view the apprentice as a rival, the relationship ends immediately; when evil dragons are involved, the ending is often fatal for the younger dragon.